¿Es suficiente la voluntad política para que tenga éxito el Presupuesto Participativo? Is the Political Will Sufficient for the Participatory Budgeting to be Successful?

Contenido principal del artículo

Cómo citar

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es confirmar empíricamente, por medio del análisis de los municipios con Presupuesto Participativo en la Comunidad Valenciana después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y 2019, que la voluntad política es un elemento fundamental para la puesta en marcha y la continuidad de las experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo. La metodología utilizada ha combinado técnicas de investigación social cualitativas y cuantitativas. Los resultados han demostrado que la voluntad política es una variable importante para la puesta en marcha de las experiencias, pero que, para su continuidad, puede ser un problema sino se incorporan otros compromisos. Sin embargo, no es una política global de ningún partido político, aunque la participación ciudadana es una política más integrada en los partidos de la izquierda, siendo estos los que ponen en marcha más experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo.

Palabras clave:

participación presupuestaria, municipios, Comunidad Valenciana, democracia participativa..Abstract

The objective of this work is to empirically confirm, through the analysis of municipalities with Participatory Budgeting in the Valencian Community after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019, that political will is a fundamental element for the implementation and continuity of Participatory Budgeting experiences. The methodology used combined qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. The results showed that political will is an important variable for the implementation of the experiments, but that its continuity can be a problem if other elements are not incorporated. The OP, however, is not a global policy of any political party, although citizen participation is a strand most found among leftist parties. Thus, these parties are the ones that most initiate Participatory Budgeting experiences.

Key words:

budget participation, municipalities, Valencian Community, participatory democracy..INTRODUCCIÓN

Hace un poco más de tres décadas en la ciudad de Porto Alegre (Brasil) nació una de las innovaciones democráticas con más reconocimiento y difusión del mundo, el Presupuesto Participativo. Siendo así reconocida por organismos internacionales como el Banco Mundial, el Fondo Monetario Internacional y ONU, y por los gobiernos de todas las latitudes, que lo han puesto en marcha y adaptado a las características propias de cada país (Pires & Pineda, 2008), habiéndose producido una difusión del modelo que ha llegado a todos los continentes. De acuerdo con lo publicado en el año 2019 en el Atlas Mundial del Orgamento Participativo, existían en ese momento más de 12.000 experiencias en marcha, siendo Europa el continente con más experiencias (4.600) y España el tercer país con mayor número (350-400) por detrás de Polonia (1840-1860) y Portugal (1686). Las medidas de aislamiento, a causa de la pandemia por el COVID-19, han llevado a muchos gobiernos a interrumpir o a dar por finalizados los procesos de presupuesto participativo en marcha, lo que ha provocado en los 30 años de funcionamiento el primer descenso del número de experiencias, hasta las 7.976 y cambios en la metodología de las que han permanecido (Dias et al., 2021). Curiosamente, las zonas del mundo que se han considerado siempre que tenían democracias con mayor participación ciudadana son las que tienen menos experiencias del PP.

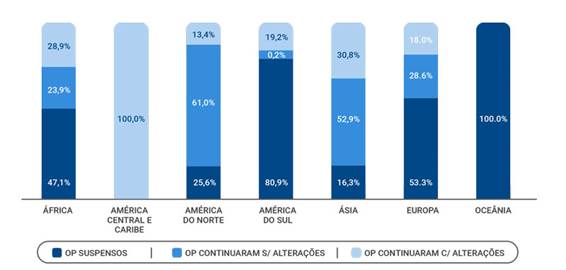

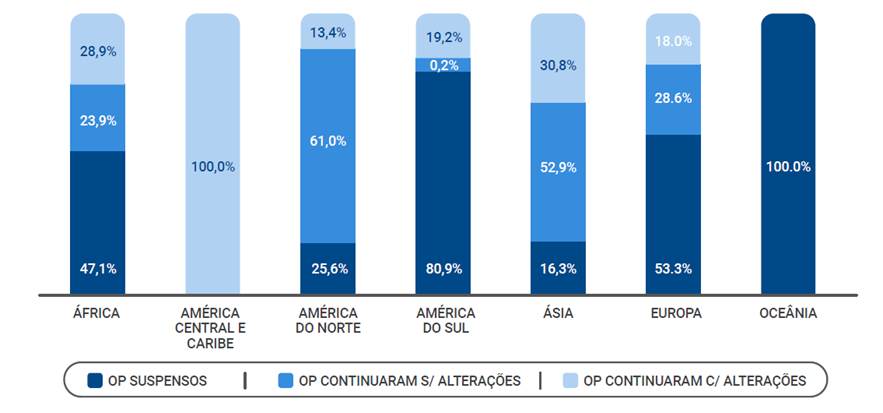

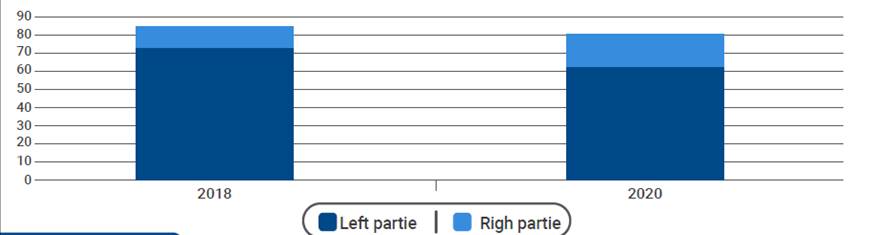

En el gráfico 1, se evidencian los cambios producidos en los continentes con referencia a las experiencias de presupuesto participativo debido a la pandemia.

Gráfico 1: Presupuestos Participativos en el mundo en tiempos de pandemia.

En España, el Presupuesto Participativo (Ganuza, 2007; Pires & Pineda, 2008; Ganuza & Francés, 2012; Mayor, 2018; Pineda & Andrade, 2018, citados por Nebot et al., 2021) fue implementado en tres municipios, los cuales son Cabezas de San Juan, Rubí y Córdoba a mediados del año 2001, todo esto porque estaban al mando de los dirigentes de la Izquierda Unida (Pineda, 2004); por esta razón, se implementó en otros municipios hasta que se llevaron a cabo las votaciones municipales para elegir a los gobernantes en el año 2015, teniendo estas como resultado la victoria por parte de la izquierda, generando múltiples experiencias después de las elecciones municipales que también fueron realizadas en el año 2019 (Nebot et al., 2021).

Al mismo tiempo que las experiencias se extendían también lo hacían los artículos, libros y comunicaciones que se publicaban sobre el tema, siendo una de las cuestiones más recurrentes las condiciones o variables que condicionan la adopción de los PP por los municipios. La literatura ha señalado durante todo este tiempo, por lo menos cuatro dimensiones principales que pueden ayudar a explicar la adopción y el mantenimiento de los PP, que son: la voluntad política de los gobernantes, el asociacionismo local, el diseño institucional y la gobernabilidad financiera (Wampler 2005, 2008; Lüchmann, 2003; Pires, 2011; Goldfrank, 2006; Horochovski & Clemente, 2012; Souza, 2015; Font et al., 2014; Fedozzi et al., 2020; Cabannes, 2020; González & Soler, 2021; Souza, 2021; Lehtonen, 2021). Siendo la voluntad política, es decir el grado de compromiso de los gobernantes de compartir con los ciudadanos el poder de decisión sobre cómo invertir los recursos del ámbito público, una de las principales variables (Fedozzi 2000; Fernández & Pineda, 2008; Lüchmann 2014; López & Gil-Jaurena, 2021).

Pero a pesar de que la voluntad política ha sido referenciada como una de las variables principales para la creación y el mantenimiento de las experiencias del PP, no se han realizado muchas investigaciones que trataran esta cuestión de una manera empírica en un territorio amplio (país, Estado o región). El propósito de este estudio analizar la variable voluntad política en un territorio (Comunidad Valenciana) a partir de dos periodos distintos: después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y 2019. Con el fin de comprobar además si la voluntad necesaria para poner en marcha y mantener una experiencia de PP es de todo el gobierno municipal o solo de algún miembro del gobierno, si la decisión responde a una estrategia global de los partidos políticos o si es una decisión individual y si su implantación responde a una cuestión ideológica, por lo cual son los partidos de izquierda los que implementan mayoritariamente experiencias de PP, o ya está generalizada (Pineda, 2010; Fedozzi et al., 2020).

En la metodología se han combinado técnicas desde la investigación social con enfoque mixto (cualitativas y cuantitativas), con la revisión y análisis de los sitios web de los ayuntamientos para conocer si existían experiencias de PP, se ha realizado también un análisis de contenido de los programas electorales de los principales partidos políticos con representación municipal en la Comunidad Valenciana y la documentación institucional junto a una revisión bibliográfica sobre el PP de autores de distintos países con especial referencia en Brasil, país origen de la experiencia.

De los respectivos análisis asociados a los resultados, se ha podido comprobar que la voluntad política, aunque necesaria, no siempre es suficiente, ya que un proceso tan complejo como el PP provoca muchas tensiones y conflictos y obliga, si se quiere que funcione y se mantenga, a convocar a más actores. También, la importancia que tiene la ideología en el momento de la implementación de una experiencia, siendo los partidos de izquierda los que mayoritariamente los implementan, aunque existan experiencias en municipios administrados por partidos políticos de centro o derecha. En este sentido, cabe mencionar que la implementación de los presupuestos participativos no hace parte de una estrategia nacional ni regional, ni de una estrategia de un partido político particular, sino que obedece a un ejercicio aislado, de una persona, que no necesariamente tiene continuidad en el ejercicio de un cargo electo de un mismo partido político. Incluso, con frecuencia se evidencia que en gobiernos locales en coalición este proceso de PP sea delegado a formaciones minoritarias, o que incluso, en corporaciones dominadas por un partido, tenga poca receptividad entre otras concejalías distintas a la que lo pone en marcha.

Referencial teórico

Desde el principio del PP, los autores que evaluaban las nuevas experiencias consideraban la voluntad política como uno de los elementos fundamentales para su aplicación y su éxito. Entendiendo la voluntad política de poner en marcha una experiencia de PP como el grado de compromiso de los gobernantes en compartir con los actores civiles el poder de decisión sobre la forma en que se destinan los recursos públicos. La razón asociada a esto, es que el presupuesto municipal siempre es elaborado y aprobado por los electos sea cual sea el sistema político local de los países, por tanto, si ellos no deciden permitir que los ciudadanos se incorporen al proceso presupuestario, no podría producirse.

Los PP nacen debido a la creación de una apuesta de un equipo político sin importar si esté respaldada o no por los demás equipos de gobierno (Allegretti et al., 2011). Los procesos de participación para poder llevarse a cabo deben tener esa voluntad política para que se tenga éxito en el proceso y el cumplimento de los compromisos hacia la población (Cabannes, 2004, citado por Mayor, 2017).

Uno de los autores que más ha escrito sobre la cuestión de la voluntad política fue Leonardo Avritzer (2009). Según Avritzer la sociedad política, en el interior de las instituciones participativas, conecta las concepciones enraizadas de participación, generadas en la formación de los partidos de izquierda y de masas. Así, la mayor o menor voluntad política de los gobernantes de introducir y dar continuidad a las instituciones participativas locales está asociada a los dilemas, generalmente enfrentados por partidos de izquierda y de masa con sesgo social democrático, entre mantener su identidad sociopolítica y simultáneamente convertirse en competitivo en el sistema político (Avritzer, 2009, p.13).

Por otro lado, Wampler (2007) desarrolla una línea interpretativa que apunta a la conjunción entre las motivaciones para la creación del PP y los dividendos políticos que podrán retornar a los protagonistas del gobierno municipal, el alcalde, los concejales y los partidos políticos que componen el gobierno. Este eje de análisis tiene como característica, el considerar al PP como elemento constitutivo del accionar político-partidista propio de las sociedades políticas locales, o sea, de manera interna a las disputas inherentes en este campo.

El planteamiento de Avritzer recibió la crítica de Romao (2011) al considerar limitada su visión del rol que juegan los partidos políticos en la estrategia de PP. Por ello Romao en trabajos posteriores en lugar de utilizar la variable psicológica "voluntad política", la substituye por la categoría de "status político del PP" en el gobierno municipal. El status político de la estrategia de PP en el contexto de la administración municipal, en su opinión, tiene una fuerte conexión con la ubicación de la estructura de gobierno, quien realiza la función de coordinación del proceso para la participación y también con el capital político de su coordinador. En cambio, Romao (2011) opina que el trabajo de Wampler (2007) abre una importante línea de investigación para profundizar en la discusión sobre los condicionantes políticos de la creación y mantenimiento del PP por parte del poder público.

Posteriormente, Mayor & Alarcón (2020), entre otros autores, señalan que además de voluntad política son necesarios otros compromisos para implementar y mantener una experiencia de PP : i) el acuerdo de todos los grupos políticos de respetar el procedimiento sin interferir las elecciones en la continuidad del presupuesto participativo; ii) el compromiso con los funcionarios públicos y trabajadores de los servicios públicos de participar en un nuevo compromiso con la sociedad; iii) el compromiso de integridad y ética pública que se recoja en un código que todos acepten y con el que se comprometan; iv) el abrir las instituciones para que la ciudadanía pueda participar y conocer las decisiones; v) tener un equipo que dinamice las prácticas colectivas del control y la priorización del gasto público; y vi) el que exista un consejo ciudadano elegido por sorteo cada año para servir de organismo de control del proceso.

Pero, aunque se han ido ampliando con el tiempo las condiciones para poner en marcha una experiencia de PP, se sigue considerando fundamental la voluntad política del gobierno municipal. En general, quizá porque la mayoría de las investigaciones son estudios de caso, no se ha planeado un análisis más amplio de esa voluntad política, que es lo que se pretende conseguir con este trabajo.

Otra cuestión importante, es analizar la ideología de los gobiernos que ponen en marcha experiencias de PP. Inicialmente estuvo fuertemente asociado con la izquierda y enmarcado como parte de una agenda de justicia social (Baiocchi & Ganuza, 2014), aunque con la difusión global del PP, esta se va difuminando al utilizarlo también gobiernos de derechas y de centro. A pesar de ello, muchos autores consideran la dimensión ideológica crucial para comprender sus posibilidades y limitaciones. El PP era en sus orígenes parte de un proyecto de izquierda que tenía como objetivo una transformación social profunda, lo que no ocurre en gobiernos de otro signo que lo utilizan como un mecanismo para la mejora de la gestión (Holdo, 2020).

La Izquierda Unida en España fue la que inició con la implementación de procesos de presupuesto participativo, en la actualidad todas las fuerzas políticas los utilizan, aunque es posible observar diferencias en sus objetivos, en el tipo de metodología empleada y en su intensidad (Mayor, 2016, p. 7). Por lo tanto, esta herramienta no es patrimonio de ninguno de los partidos políticos, aunque siguen siendo mayoritarias las experiencias en municipios gobernados por partidos o coaliciones de izquierda (Pineda, 2010; Cernadas et al., 2013; Galais et al., 2011; Mayor & Alarcón, 2020).

Basándonos en lo que se ha expuesto, podemos formular las hipótesis de investigación que se relacionan a continuación:

H1: Los Presupuestos Participativos en la Comunidad Valenciana se ponen en marcha por la voluntad política del alcalde o de algún miembro del Gobierno municipal.

H2: El PP no es una política global de los partidos políticos.

H3: Son mayoritariamente los partidos de izquierda los que ponen en marcha experiencias de PP en la Comunidad Valenciana.

H4: Las experiencias desaparecen al cambiar el signo político del gobierno municipal.

METODOLOGÍA

La metodología utilizada combina técnicas de investigación social cualitativas y cuantitativas mediante las cuales se puede conocer la situación del Presupuesto Participativo en los municipios de la Comunidad Valencia en dos periodos diferentes, después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y las de 2019, y compararlas. Para ello, se han revisado y analizado las páginas web de los ayuntamientos, los programas electorales de los principales partidos políticos con representación municipal en la Comunidad Valenciana y la documentación institucional junto a la necesaria revisión de la literatura de autores de distintos países.

El objeto de análisis de la investigación han sido los municipios de más de 4.000 habitantes de la Comunidad Valenciana, una de las 17 comunidades en que se divide España, habiéndose elegido el corte en este número al no haber encontrado experiencias en municipios con un censo inferior a esta cifra.

Figura 1: Mapa político de España

La Comunidad Valenciana es la cuarta comunidad autónoma de España por población y representa el 10,7% de la población del país, estando dividida en tres provincias: Alicante, Castellón y Valencia. Esta comunidad ha estado durante veinte años gobernada por el Partido Popular. Además, es en estos momentos una de las comunidades españolas con un mayor número de experiencias de PP.

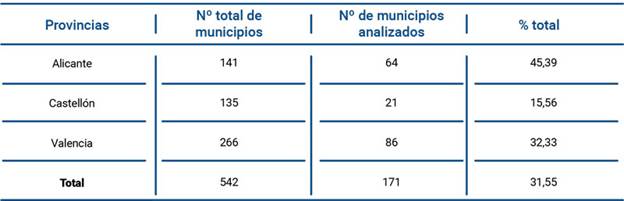

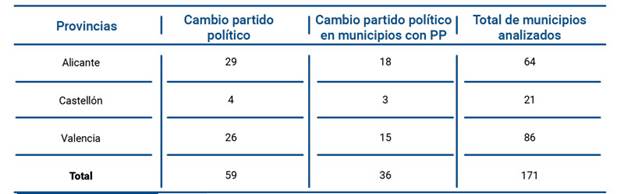

En la Tabla 1 se ofrecen datos correspondientes al número total de municipios por provincias de la Comunidad Valenciana, el número total de municipios investigados, que asciende a 171 y el porcentaje de municipios analizados.

Fuente: elaboración propia.

Tabla 1: Número total de municipios por provincias y municipios analizados.

Estos datos nos indican que se han analizado el 31.55% del total de municipios de la Comunidad Valenciana, siendo el porcentaje mayor en la provincia de Alicante (45,39%). Eso ocurre porque las otras dos provincias tienen un número mayor de municipios de menos de 4.000 habitantes, es decir de municipios de tamaño pequeño.

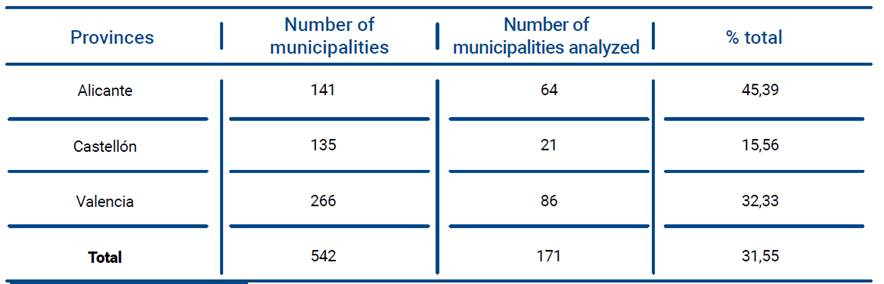

En la Tabla 2 podemos ver la población total y por provincias de la Comunidad Valenciana, la población con PP y el porcentaje de población con PP del total de población.

Fuente: elaboración propia a partir de datos de población del Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE).

Tabla 2: Población de la C. Valenciana y población con PP.

Viendo los datos de población, se aprecia que aunque son el 31,55% de municipios los que tienen PP suponen el 92,25% de la población total de la comunidad. Siendo Valencia la que tiene un porcentaje más bajo y Alicante, con municipios de mayor tamaño, la que tiene un porcentaje más alto.

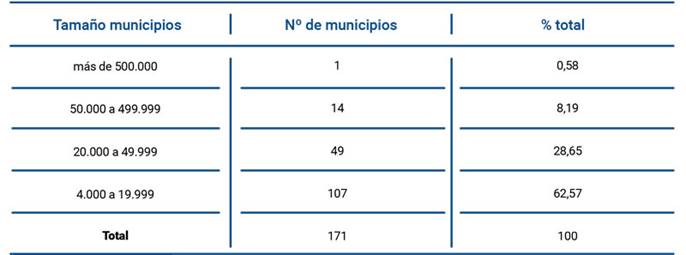

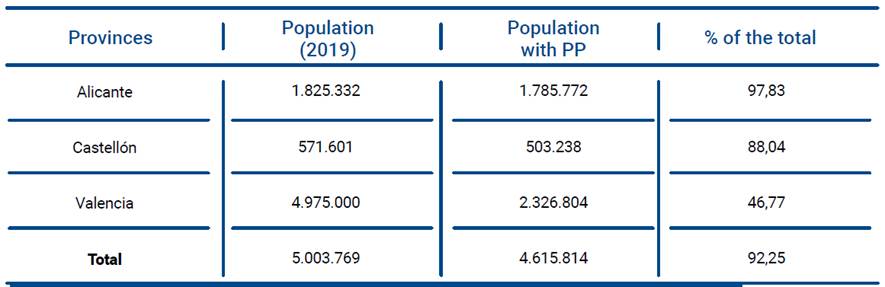

En la Tabla 3 vemos el tamaño de los municipios analizados y el porcentaje que les corresponde del total de ellos.

Fuente: elaboración propia.

Tabla 3: Población de la C. Valenciana y población con PP.

En cuanto al tamaño de los municipios se puede apreciar que la mayoría (62,57%) son municipios que oscilan entre 4.000 y 19.999 habitantes, es decir de tamaño medio bajo.

El trabajo de campo se realizó en dos etapas: la primera supuso la recogida de los datos y la segunda su tratamiento. Los datos fueron recogidos por medio de un proceso de observación sistemática de los portales municipales. La cronología de recogida de los datos se realizó en dos períodos: el primero de diciembre de 2018 a enero de 2019 y el segundo de diciembre de 2020 a enero de 2021.

Resultados y discusión

En el Atlas Mundial del Orgamento Participativo (Días et al., 2019), cuyo objetivo fundamental es inventariar las experiencias de PP en el mundo, se encontraron 12.000 experiencias, siendo Europa la región del mundo donde existían más experiencias (4.600), número que ha descendido durante el tiempo de la pandemia (Dias et al., 2021). En España el número de experiencias han ido creciendo durante los 20 años que llevan entre nosotros, aunque con fuertes oscilaciones, siendo a partir de las elecciones municipales de 2015 cuando se ha producido un mayor crecimiento, debido, entre otras razones, a la llegada de los llamados gobiernos del cambio. Los candidatos municipales se presentaban como aquellos con nuevas prácticas en la manera de hacer política, que suponía la implicación ciudadana en la gestión a través del desarrollo de espacios compartidos de información y toma de decisiones, no obstante, sería falso afirmar que ellos han iniciado las políticas públicas participativas en España (Mérida & Tellería, 2021).

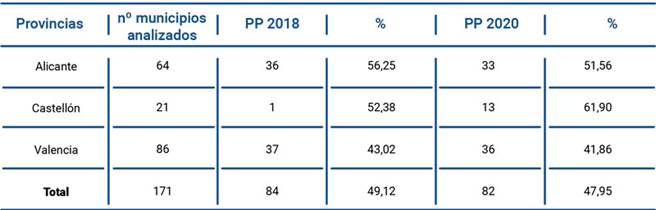

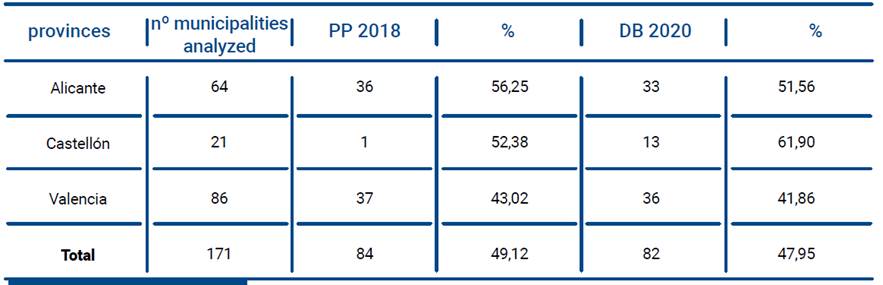

Según los datos del Atlas de 2019, la Comunidad Valenciana tenía entre un 20 y un 25% de las experiencias españolas de PP, número que, como se puede ver en la Tabla 4, se ha mantenido después de las últimas elecciones municipales, aunque con un pequeño descenso y que suponen casi la mitad de los municipios estudiados. Lo que demuestra que existe un gran interés en esta comunidad por poner en marcha experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo. Sería interesante analizar la situación después de las próximas elecciones de 2023, para conocer si se mantienen las experiencias a pesar de todo el periodo de pandemia.

Fuente: elaboración propia.

Tabla 4: Municipios con Presupuesto Participativo en 2018 y 2020 en la C. Valenciana

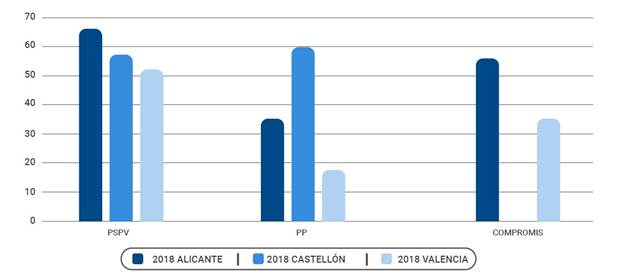

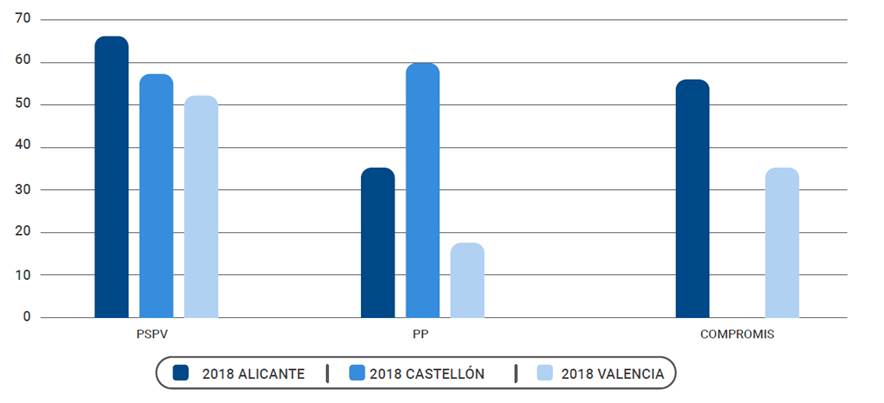

Si tenemos en cuenta el porcentaje de municipios gobernados, a partir de 2015, por uno de los tres partidos políticos mayoritarios en la comunidad (PSPV, Partido Popular y Compromis) en relación al número de municipios analizados que gobiernan en cada una de las provincias vemos en el Gráfico 2 que en 2018 los dos partidos de izquierda (PSPV y Compromis) tienen mayor representación en la provincia de Alicante y que en cambio el Partido Popular tiene mayor peso en la provincia de Castellón, que es la más pequeña de las tres provincias.

Gráfico 2: Porcentaje de municipios analizados gobernados por cada partido político en 2018

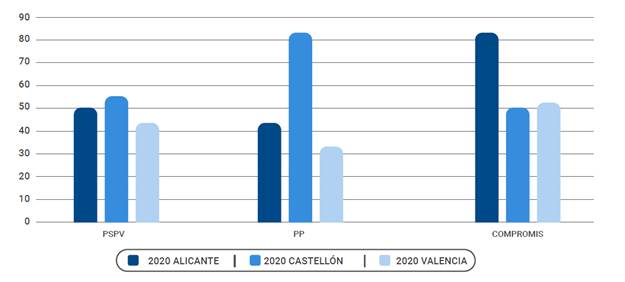

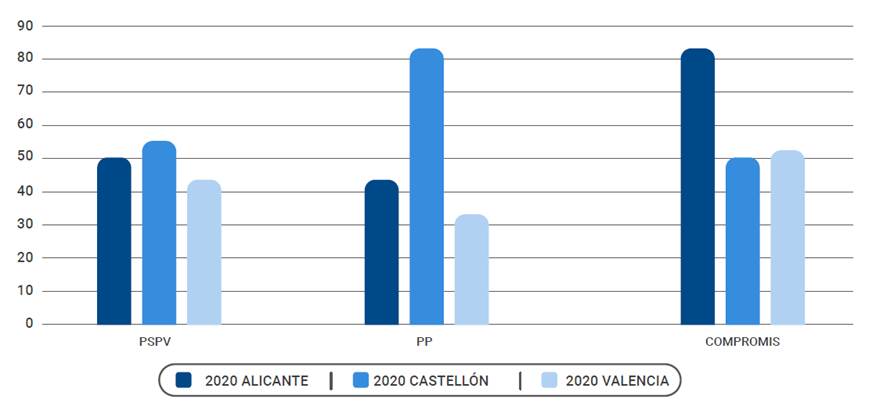

Gráfico 3: Porcentaje de municipios analizados gobernados por cada partido político en 2020

La situación cambia después de las elecciones de 2020, recuperando en Alicante y Valencia el poder que el Partido Popular había tenido durante los últimos veinte años, el PSPV desciende en las tres provincias y Compromis lo aumenta en las tres. A pesar de estos cambios no se produce una gran variación en el número de experiencias de PP

A pesar de la disminución del porcentaje de municipios gobernados por el PSPV después de las elecciones de 2019 no descendió tanto la población gobernada por este partido, que paso del 54,7% en 2015 al 49,7% en 2019. El Partido Popular, a pesar de aumentar el porcentaje en la provincia de Castellón, descendió del 8% al 6,3% de la población. Solo Compromis aumentó su porcentaje de población, del 37 al 44%, gracias a la ventaja conseguida en Alicante y Castellón. Lo que supone que, aunque el PSPV perdió el gobierno de algunos municipios, sigue gobernando a casi el 50% de la población de la comunidad.

Pero estos datos no nos sirven para conocer si se han producido cambios en los gobiernos municipales y si estos cambios han influido en el mantenimiento o desaparición de las experiencias de PP. Para ello, se deben comprender los diferentes cambios políticos producidos de una elección y si esos cambios han influido en los PP.

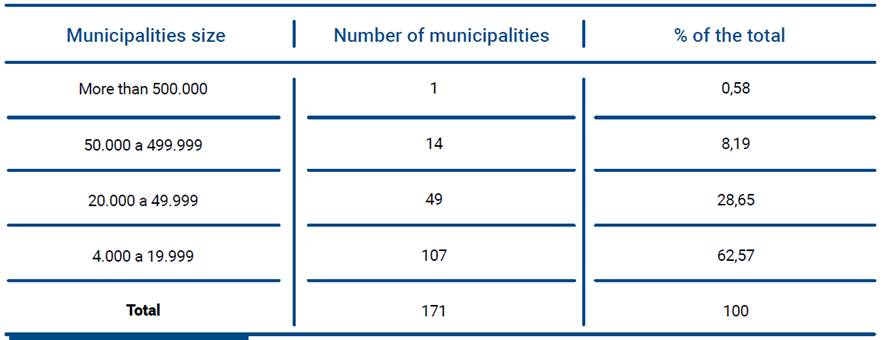

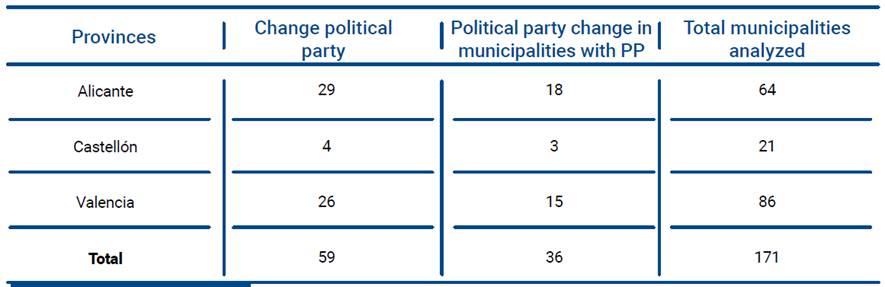

En la Tabla 5 se pueden apreciar los cambios producidos en los diferentes municipios analizados después de las elecciones del 2019, tanto en los municipios que tenían PP como los que no lo tenían.

Fuente: elaboración propia.

Tabla 5: Cambios de partido político después de las elecciones municipales de 2019

En los sufragios de orden municipal de mayo de 2019, 59 municipios de la Comunidad Valenciana cambiaron el signo político de sus alcaldes, lo que supone el 34,5% de los municipios analizados, siendo la provincia de Alicante donde se han producido más cambios (45,31%) y la de Castellón donde menos (19%). En cambio, en aquellos municipios en que existe una experiencia de PP se han producido menos cambios, solo el 21% del total de municipios analizados han cambiado su signo político. Habría que analizar en profundidad si el PP ha sido un factor de continuidad para el partido político gobernante o si las razones han sido otras.

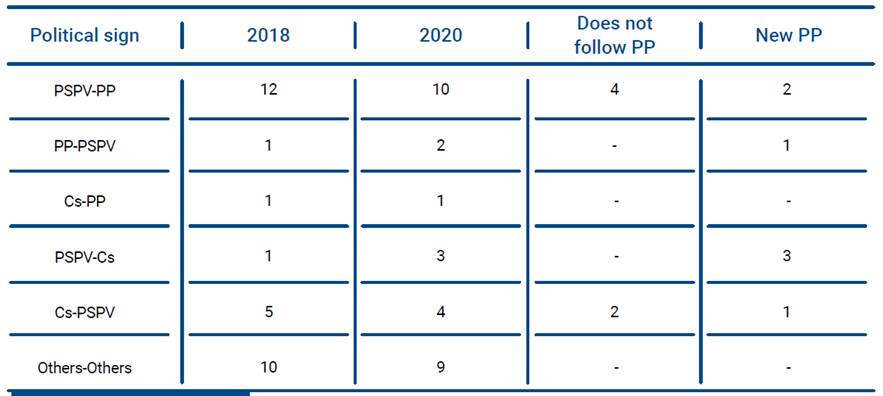

De estos cambios, los más significativos como se puede ver en la Tabla 6, al tratarse de partidos de izquierda a un partido de derechas, son los del Partido Socialista de la Comunidad Valenciana (PSPV) y Compromis al Partido Popular. En el caso del cambio del PSPV al Partido Popular (14 municipios) cuatro de las experiencias de PP no han continuado, pero se han puesto en marcha dos experiencias nuevas. De Compromis al Partido Popular solo se ha producido un cambio y allí se ha mantenido la experiencia de PP. En los cambios entre el PSPV y Compromis (3 municipios) hemos apreciado que se ha mantenido la experiencia que había y se han creado en los municipios que no tenían. No ha ocurrido lo mismo cuando los municipios han pasado de ser gobernados por Compromis a serlo por el PSPV, ya que dos de las experiencias en marcha han finalizado. Lo que viene a demostrar que no siempre el cambio de signo político del gobierno municipal supone la eliminación de la experiencia, aunque se da con más frecuencia cuando pasa de un gobierno de izquierda a uno conservador. En este punto, también sería interesante conocer las razones del cambio de signo político del gobierno municipal y de qué forma ha influido tanto en la continuidad del proceso de PP como en sus objetivos y metodología.

Fuente: elaboración propia.

Tabla 6: Cambios en el signo político de los gobiernos municipales

Hemos querido analizar también, para conocer si la decisión política de poner en marcha o continuar una experiencia de PP dependía del signo político del alcalde, aquellos casos en los que se mantenía el mismo partido político en el gobierno municipal, pero que a pesar de ello se realizaron cambios después de las elecciones de 2019. Hemos encontrado diez municipios que daban por finalizadas experiencias de PP y otros diez que las ponían en marcha, manteniendo el mismo partido el gobierno municipal. En el caso de los municipios que dieron por finalizadas las experiencias de PP después de 2019 nos hemos encontrado que la mayoría ha sido por cambios en la persona que llevaba la experiencia, ya sea el alcalde o un concejal. En el caso de los concejales, en uno de ellos era del mismo partido que el alcalde, aunque en la mayoría de los casos eran concejales de otro partido que gobernaban en coalición con el partido mayoritario, mediante un pacto de legislatura, y que no salieron elegidos en la siguiente convocatoria de elecciones. Algo similar ocurre cuando se decide poner en marcha una experiencia de PP. Otras razones para la finalización del proceso son la dificultad de gestionar las propuestas o la decisión de que el dinero que se utilizaba para el PP vaya a una sola propuesta. En el único caso que hemos encontrado del Partido Popular, la explicación de la experiencia es la contratación de una consultora para implementar una iniciativa tipo proyecto asociado a transparencia y gobierno abierto, proyecto en el que engloban al PP.

Para conocer si la decisión de poner en marcha experiencias de PP es una propuesta global de los partidos políticos o son propuestas aisladas de políticos municipales, hemos realizado un análisis de los programas marco municipales de los tres principales partidos políticos con representación en la Comunidad Valenciana de las elecciones de 2015 y 2019, habiendo apreciado que en ninguno de ellos se hace una referencia clara al PP ni una propuesta de aplicación, como si ocurría en otras elecciones municipales anteriores. Esto no quiere decir que en el programa electoral específico de algunos ayuntamientos no se haga referencia al PP, pero si demuestra que el PP no es una política general de partido.

A pesar de ello, existen diferencias entre unos programas y otros. En el del PSOE de 2015 se habla de hacer pública la información relativa a las partidas presupuestarias y en el apartado de los jóvenes se refiere a la posibilidad de hacer llegar sus propuestas a los presupuestos participativos. En el de 2019 se hace referencia a la transparencia de la cuentas públicas, a la celebración de asambleas ciudadanas en las que se rendirán cuentas de la gestión y se recabarán quejas, sugerencias o aportaciones por parte de la ciudadanía y, también se habla de que se someterá a información y debate el borrador de los presupuestos municipales que reservara una cantidad anual para inversiones que serán decididas directamente por los vecinos en procesos participativos, en los que se seleccionarán y votarán las propuestas que finalmente se llevarán a las partidas presupuestarias definitivas. Esto último, aunque no reciba el nombre de PP es realmente un PP.

En el de Compromis no hay referencia al PP, pero si a la participación ciudadana cuando se refieren tanto a su modelo económico como a las distintas políticas públicas. Además, señalan que impulsaran una Ley de Gobierno Abierto, que abra las puertas de la administración a la ciudadanía, que fomente su participación en la toma de decisiones y que garantice la transparencia en la gestión del dinero público.

En el programa del Partido Popular de 2015 no existe ninguna referencia al PP ni a la participación en el presupuesto. Sobre la participación, señalan que fomentarán la mejora y la aplicación de instrumentos normativos y mecanismos de participación ciudadana para lograr una mayor interactuación entre los responsables municipales y los vecinos, haciendo hincapié en la utilización para ello de las TIC. En el de 2019 no existen esas referencias, es un programa enfocado totalmente en la economía.

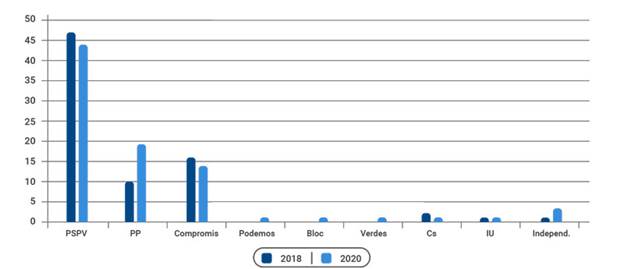

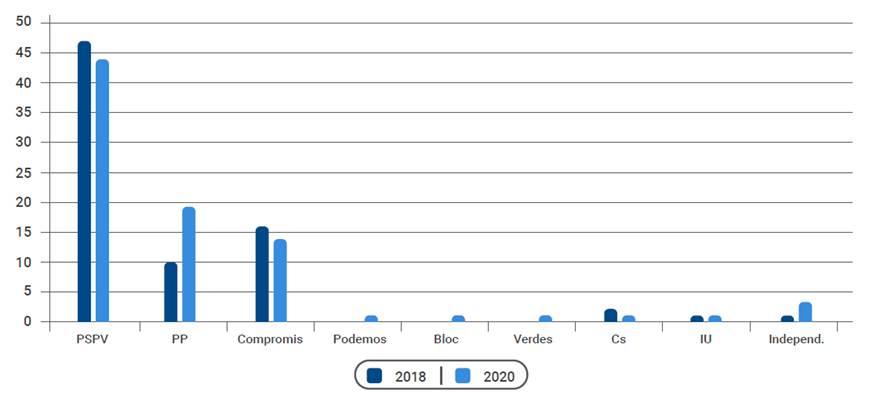

Otra cuestión que analizamos, es si la decisión política de poner en marcha una experiencia de PP depende del signo político del gobierno municipal, si son aquellos municipios gobernados por partidos de izquierda los que más aplican estos proyectos. Como se puede apreciar en el gráfico 4 el mayor número de experiencias en las dos legislaturas se encuentran en municipios gobernados por el PSPV (58,75% y 53,66%) aunque después de las elecciones de 2019 el número de experiencias disminuyeron (10 experiencias).

Gráfico 4: Experiencias de PP por partido político en 2018-2020

Los otros dos partidos que tienen un número importante de experiencias son Compromis que pasa de 14 a 16 experiencias y el Partido Popular que pasó de 10 a 19 experiencias, lo que supuso un incremento importante.

Como se puede apreciar, existen experiencias impulsadas tanto por partidos de izquierdas como conservadores, lo que demuestra la heterogeneidad ideológica del proyecto. Aunque la mayoría se dan en municipios gobernados por partidos de izquierda, como se puede ver en el gráfico 5, lo que ha ocurrido desde el principio de la implementación de experiencias de PP en España (Pineda, 2010). Sin olvidar, además, que fue un partido de izquierdas, Izquierda Unida, el que trajo las primeras experiencias de PP a los municipios españoles, teniendo como referencia principal la ciudad de Córdoba.

Gráfico 5: Número de experiencias de PP según orientación ideológica

Estos datos confirman que son los partidos de izquierda los que mayoritariamente ponen en marcha experiencias de PP, aunque ya existen partidos de otro sesgo político que lo hacen, aunque minoritariamente.

Estos datos vienen a confirmar todas las hipótesis planteadas. La primera es que todas las experiencias de la Comunidad se ponen en marcha en consonancia con la voluntad política del gobierno, ya sea el alcalde o un concejal. Concejal que puede ser del partido mayoritario o del partido minoritario en el caso de los gobiernos de coalición. La segunda es que su puesta en marcha no forma parte de una política general planteada por ningún partido político, sino que son propuestas individuales de alcaldes o concejales electos. La tercera es que son los municipios gobernados por partidos políticos con tendencia de izquierda (PSPV o Compromis) los que mayoritariamente ponen en marcha procesos de PP, aunque cada vez hay más municipios gobernados por el Partido Popular que también lo hacen. Por último, es importante señalar que la mayoría de las veces las experiencias desaparecen al cambiar el signo político del gobierno municipal, pero también puede producirse por otras razones.

Conclusiones

Todas las experiencias analizadas en la Comunidad Valenciana nacen de una decisión política del gobierno municipal, ya que no existe en el ordenamiento jurídico español, exceptuamos la Ley de "Grandes Ciudades", ningún precepto que incluya la participación de los ciudadanos en la toma de decisiones presupuestarias, como sí ocurre en otros países como Perú desde el año 2003, República Dominicana desde 2007 o Corea del Sur a partir del 2011.

Esta decisión política la puede impulsar el alcalde o un concejal, lo que significa que puede o no contar con el apoyo de todo el gobierno. En el caso de algunos gobiernos de coalición el socio minoritario suele ser el que impulse el proyecto de PP, con las consecuencias negativas para su funcionamiento que esta situación provoca, al sentir los demás miembros del gobierno que es una imposición. Otro aspecto negativo que se percibe en algunas experiencias es la identificación del proceso con el partido que la pone en marcha, lo que provoca una pérdida de su potencial y su desaparición cuando cambia el signo político del gobierno municipal. Para solucionar este tema sería interesante que el equipo de gobierno implicara en el proyecto a la oposición.

Y aunque el impulso de los PP responde en todos los municipios a una cierta voluntad política, pues de lo contrario no se llevarían a cabo, existe en general poco compromiso político. Es evidente al ver que este tipo de experiencias acostumbran a ser residuales dentro de las estructuras de gobierno, encargándose, en la mayoría de los casos, de su gestión el concejal o concejala de participación ciudadana. Además, suele existir poca implicación de los distintos departamentos de la administración local afectados por los resultados del proceso, hecho que dificulta enormemente tanto el desarrollo del proceso como la ejecución de sus resultados.

En los programas municipales analizados, de las elecciones de 2015 y 2019, de los tres principales partidos políticos de la Comunidad Valenciana no se hace ninguna referencia concreta al Presupuesto Participativo. Lo que demuestra que poner en marcha una experiencia de PP no es una estrategia global de ningún partido político. Sin embargo, en el programa marco del PSOE para las elecciones municipales de 2019 se habla de que se someterá a información y debate el borrador de los presupuestos municipales que reservara una cantidad anual para inversiones que serán decididas directamente por los vecinos en procesos participativos, en los que seleccionarán y votarán las propuestas que finalmente se llevarán a las partidas presupuestarias definitivas. Esto último, aunque no reciba el nombre de PP es realmente un PP.

A pesar de no hacerse mención al presupuesto participativo en ninguno de los programas de los tres partidos, es importante señalar las diferencias existentes entre los programas del PSPV y Compromis y el del Partido Popular en lo referente a la participación ciudadana, en los dos primeros hay referencias claras sobre el papel que los ciudadanos deben tener en la gestión y el gobierno de los municipios y en los del Partido Popular hay una mención escasa sobre el tema y cuando se hace tiene un carácter muy normativo y relacionado con las TIC. A pesar de ello, los tres partidos ponen en marcha experiencias en alguno de los municipios que gobiernan.

Los datos también confirman que son los partidos de izquierda son los que mayoritariamente ponen en marcha experiencias de PP en la Comunidad Valenciana (72%), aunque partidos de otro sesgo político también lo hacen, aunque más minoritariamente. Percibiéndose claras diferencias en los objetivos de las experiencias según la ideología del gobierno municipal.

Se observa además, que aquellos PP que surgen de una decisión política basada más en una tendencia o "moda" que, en una convicción sobre las ventajas de la participación de los ciudadanos, es decir que lo consideran más una herramienta técnica neutra de buen gobierno más que una institución política (Wampler & Goldfranck, 2022, p. 12), tienden al uso de internet como única vía de participación, utilizando las TIC solo para la recogida de propuestas, como si fuera un buzón.

La "politización" del PP, como ya hemos señalado, tiene aspectos tanto negativos como positivos. Tener respaldo político puede fortalecer el compromiso y asegurar recursos adecuados, pero también crea vulnerabilidades críticas que pueden afectar la sostenibilidad a largo plazo. Se ha comprobado al analizar los datos, que la identificación de la propuesta con un partido político concreto puede arruinar su futuro, algunas experiencias han desaparecido no porque no funcionaran bien sino porque al ganar las siguientes elecciones otro partido político este no ha querido que le relacionaran con el proyecto de sus antecesores.

La centralidad de la voluntad política puede hacer un proceso de PP más "vulnerable" frente a otros procesos participativos más institucionalizados. Encontrar el equilibrio adecuado entre todos estos aspectos puede ser un factor clave de éxito en los procesos de PP en todas las partes del mundo.

Por último, señalar lo que indica Yves Cabannes (2004): "La voluntad tiene que mantenerse durante todo el proceso, pero de manera fundamental debe concretarse en el cumplimiento de los compromisos presupuestales contraídos con la población" (p. 30). Si no ocurre de ese modo, el proceso tiende a crear desconfianza entre la ciudadanía y termina por desaparecer.

Abstract

The objective of this work is to empirically confirm, through the analysis of municipalities with Participatory Budgeting in the Valencian Community after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019, that political will is a fundamental element for the implementation and continuity of Participatory Budgeting experiences. The methodology used combined qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. The results showed that political will is an important variable for the implementation of the experiments, but that its continuity can be a problem if other elements are not incorporated. The OP, however, is not a global policy of any political party, although citizen participation is a strand most found among leftist parties. Thus, these parties are the ones that most initiate Participatory Budgeting experiences.

Key words:

budget participation, municipalities, Valencian Community, participatory democracy..Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es confirmar empíricamente, por medio del análisis de los municipios con Presupuesto Participativo en la Comunidad Valenciana después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y 2019, que la voluntad política es un elemento fundamental para la puesta en marcha y la continuidad de las experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo. La metodología utilizada ha combinado técnicas de investigación social cualitativas y cuantitativas. Los resultados han demostrado que la voluntad política es una variable importante para la puesta en marcha de las experiencias, pero que, para su continuidad, puede ser un problema sino se incorporan otros compromisos. Sin embargo, no es una política global de ningún partido político, aunque la participación ciudadana es una política más integrada en los partidos de la izquierda, siendo estos los que ponen en marcha más experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo.

Palabras clave:

participación presupuestaria, municipios, Comunidad Valenciana, democracia participativa..INTRODUCTION

A little over three decades ago in the city of Porto Alegre (Brazil) one of the most recognized and widely spread democratic innovations in the world was born, the Participatory Budget. Being thus recognized by international organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the UN, and by governments of all latitudes, which have implemented it and adapted it to the characteristics of each country (Pires & Pineda, 2008), having produced a diffusion of the model that has reached all continents. According to what was published in 2019 in the World Atlas of the Participatory Orçamento , there were at that time more than 12,000 experiences underway, with Europe being the continent with the most experiences (4,600) and Spain the third country with the highest number (350-400). ) behind Poland ( 1840-1860) and Portugal (1686) .The isolation measures, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have led many governments to interrupt or terminate the ongoing participatory budgeting processes, which has caused the first decrease in the number of budgets in the 30 years of operation. of experiences, up to 7,976 and changes in the methodology of those that have remained (Dias et al., 2021). Interestingly, the areas of the world that have always been considered to have democracies with greater citizen participation are the ones with the least experience of the PP.

Graph 1 shows the changes produced in the continents with reference to the experiences of participatory budgeting due to the pandemic.

Figure 1: Participatory Budgets in the world in times of pandemic

In Spain, the Participatory Budget (Ganuza, 2007; Pires & Pineda, 2008; Ganuza & Francés, 2012; Mayor, 2018; Pineda & Andrade, 2018, cited by Nebot et al., 2021) was implemented in three municipalities, which they are Cabezas de San Juan, Rubí and Córdoba in mid-2001, all this because they were commanded by the leaders of the United Left (Pineda, 2004); for this reason, it was implemented in other municipalities until municipal voting was held to elect the rulers in 2015, resulting in the victory of the left, generating multiple experiences after the municipal elections that also were carried out in 2019 (Nebot et al., 2021).

While the experiences spread, so did the articles, books and communications that were published on the subject, one of the most recurrent issues being the conditions or variables that condition the adoption of the PP by the municipalities. The literature has pointed out during all this time, at least four main dimensions that can help explain the adoption and maintenance of PP, which are: the political will of the rulers, local associationism, institutional design and financial governance (Wampler 2005, 2008; Lüchmann , 2003; Pires, 2011; Goldfrank , 2006; Horochovski & Clemente, 2012; Souza, 2015; Font et al., 2014; Fedozzi et al., 2020; Cabannes , 2020; González & Soler, 2021; Souza, 2021; Lehtonen, 2021). Being the political will, that is, the degree of commitment of the rulers to share with the citizens the power of decision on how to invest the resources of the public sphere, one of the main variables (Fedozzi 2000; Fernández & Pineda, 2008; Lüchmann 2014; López & Gil-Jaurena, 2021).

But despite the fact that political will has been referenced as one of the main variables for the creation and maintenance of PP experiences, not much research has been carried out that deals with this issue empirically in a wide territory (country, state or region). The purpose of this study is to analyze the variable political will in a territory (Valencian Community) from two different periods: after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019. In order to also verify if the necessary will to start up and maintain a PP experience is that of the entire municipal government or only of a member of the government, if the decision responds to a global strategy of the political parties or if it is an individual decision and if its implementation responds to an ideological issue, for which they are the left-wing parties are the ones that mostly implement PP experiences, or it is already generalized (Pineda, 2010; Fedozzi et al., 2020).

In the methodology, techniques have been combined from social research with a mixed approach (qualitative and quantitative), with the review and analysis of the websites of the municipalities to know if there were experiences of PP, a content analysis of the electoral programs of the main political parties with municipal representation in the Valencian Community and the institutional documentation together with a bibliographic review on the PP of authors from different countries with special reference to Brazil, the country of origin of the experience.

From the respective analyzes associated with the results, it has been verified that political will, although necessary, is not always sufficient, since a process as complex as the PP causes many tensions and conflicts and requires, if it is to function and be maintained, to summon more actors. Also, the importance of ideology at the time of the implementation of an experience, being the leftist parties the ones that mostly implement them, although there are experiences in municipalities administered by political parties of the center or right. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that the implementation of participatory budgets is not part of a national or regional strategy, nor of a strategy of a particular political party, but rather is due to an isolated exercise, of a person, who does not necessarily have continuity in the exercise of an elected position of the same political party. It is even frequently evident that in local governments in coalition this PP process is delegated to minority formations, or that even, in corporations dominated by a party, it has little receptivity among other departments other than the one that starts it.

Theoretical reference

From the beginning of the PP, the authors who evaluated the new experiences considered political will as one of the fundamental elements for its application and success. Understanding the political will to launch a PP experience as the degree of commitment of the rulers to share with civil actors the power of decision on the way in which public resources are allocated. The reason associated with this is that the municipal budget is always prepared and approved by the elected, regardless of the local political system of the countries, therefore, if they do not decide to allow citizens to join the budget process, it could not occur.

The PP are born due to the creation of a bet of a political team regardless of whether it is supported or not by the other government teams (Allegretti et al., 2011). In order to be carried out, the participation processes must have that political will so that the process is successful and the fulfillment of the commitments towards the population (Cabannes , 2004, cited by Mayor, 2017).

One of the authors who has written the most on the issue of political will was Leonardo Avritzer (2009). According to Avritzer, political society, within participatory institutions, connects the rooted conceptions of participation, generated in the formation of leftist and mass parties. Thus, the greater or lesser political will of the rulers to introduce and give continuity to local participatory institutions is associated with the dilemmas, generally faced by leftist and mass parties with a social democratic bias, between maintaining their sociopolitical identity and simultaneously becoming competitive in the political system (Avritzer , 2009, p.13).

On the other hand, Wampler (2007) develops an interpretive line that points to the conjunction between the motivations for the creation of the PP and the political dividends that may return to the protagonists of the municipal government, the mayor, the councilors and the political parties that make up the government. This axis of analysis has the characteristic of considering the PP as a constitutive element of the political-partisan actions of local political societies, that is, internally to the disputes inherent in this field.

Avritzer’s approach was criticized by Romão (2011) who considered his vision of the role played by political parties in the PP strategy to be limited. That is why Romão in later works, instead of using the psychological variable “political will”, substitutes it for the category of “political status of the PP “ in the municipal government. The political status of the PB strategy in the context of the municipal administration, in his opinion, has a strong connection with the location of the government structure, which performs the function of coordinating the process for participation, and also with political capital. of your coordinator. On the other hand, Romão (2011) believes that the work of Wampler (2007) opens an important line of research to deepen the discussion on the political conditioning factors of the creation and maintenance of the PP by the public power.

Subsequently, Mayor & Alarcón (2020), among other authors, point out that in addition to political will, other commitments are necessary To implement and maintain a PP experience: i) the agreement of all the political groups to respect the procedure without interfering with the elections in the continuity of the participatory budget ; ii) the commitment to public officials and public service workers to participate in a new commitment to society; iii) the commitment to integrity and public ethics that is included in a code that everyone accepts and commits to; iv) opening the institutions so that citizens can participate and know the decisions; v) have a team that stimulates the collective practices of control and prioritization of public spending; and vi) the existence of a citizen council elected by lottery each year to serve as a control body for the process.

But, although the conditions for launching a PP experience have been expanded over time, the political will of the municipal government is still considered essential. In general, perhaps because most of the investigations are case studies, a broader analysis of that political will has not been planned, which is what this work is intended to achieve.

Another important issue is to analyze the ideology of the governments that launch PP experiences. Initially it was strongly associated with the left and framed as part of a social justice agenda (Baiocchi & Ganuza, 2014), although with the global spread of the PP, this is fading as it is also used by right-wing and center governments. Despite this, many authors consider the ideological dimension crucial to understand its possibilities and limitations. The PP was originally part of a leftist project that aimed at profound social transformation, which does not happen in governments of another sign that use it as a mechanism to improve management (Holdo, 2020).

The United Left in Spain was the one that began with the implementation of participatory budget processes, currently all political forces use them, although it is possible to observe differences in their objectives, in the type of methodology used and in their intensity (Greater , 2016, p. 7). Therefore, this tool is not the property of any of the political parties, although the experiences in municipalities governed by left-wing parties or coalitions continue to be the majority (Pineda, 2010; Cernadas et al., 2013; Galais et al., 2011; Mayor & Alarcon, 2020).

Based on what has been exposed, we can formulate the following research hypotheses:

H1: Participatory Budgets in the Valencian Community are launched by the political will of the mayor or some member of the municipal government.

H2: The PP is not a global policy of political parties.

H3: It is mostly the leftist parties that launch PP experiences in the Valencian Community.

H4: The experiences disappear when the political sign of the municipal government changes.

Methodology

The methodology used combines qualitative and quantitative social research techniques through which the situation of the Participatory Budget in the municipalities of the Valencia Community can be known in two different periods, after the municipal elections of 2015 and those of 2019, and compare them. For this, the web pages of the municipalities, the electoral programs of the main political parties with municipal representation in the Valencian Community and the institutional documentation have been reviewed and analyzed together with the necessary review of the literature of authors from different countries.

The object of analysis of the investigation has been the municipalities of more than 4,000 inhabitants of the Valencian Community, one of the 17 communities in which Spain is divided, having chosen the cut in this number as no experiences were found in municipalities with a lower census to this figure 2.

Figure 2: Political map of Spain.

The Valencian Community is the fourth autonomous community in Spain by population and represents 10.7% of the country's population, being divided into three provinces: Alicante, Castellón and Valencia. This community has been governed by the Popular Party for twenty years. In addition, it is currently one of the Spanish communities with the largest number of PP experiences.

Table 1 offers data corresponding to the total number of municipalities by province of the Valencian Community, the total number of municipalities investigated, which amounts to 171, and the percentage of municipalities analyzed.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 1: Total number of municipalities by provinces and municipalities analyzed.

These data indicate that 31.55% of the total municipalities of the Valencian Community have been analyzed, the highest percentage being in the province of Alicante (45.39%). This occurs because the other two provinces have a greater number of municipalities with less than 4,000 inhabitants, that is, small-sized municipalities.

In Table 2 we can see the total population and by provinces of the Valencian Community, the population with PP and the percentage of the population with PP of the total population.

Source: own elaboration based on population data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) (2021).

Table 2: Population of the C. Valenciana and population with PP.

Looking at the population data although 31.55% of the municipalities have PP, they account for 92.25% of the total population of the community. Valencia being the one with the lowest percentage and Alicante, with larger municipalities, the one with the highest percentage.

In Table 3 we see the size of the municipalities analyzed and the percentage that corresponds to them from the total of them.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 3: Size of the municipalities under analysis.

Regarding the size of the municipalities, the majority (62.57%) are municipalities that range between 4,000 and 19,999 inhabitants, that is, of medium-low size.

The field work was carried out in two stages: the first involved the collection of data and the second its treatment. The data was collected through a process of systematic observation of the municipal portals. The data collection chronology was carried out in two periods: the first from December 2018 to January 2019 and the second from December 2020 to January 2021.

Results and Discussion

n the World Atlas of the Participatory Orçamento (Días et al., 2019), whose main objective is to inventory the experiences of PP in the world, 12,000 experiences were found, with Europe being the region of the world where there were more experiences (4,600), number which has decreased during the time of the pandemic (Dias et al., 2021). In Spain, the number of experiences has been growing during the 20 years that they have been with us, although with strong oscillations, being from the municipal elections of 2015 when there has been a greater growth, due, among other reasons, to the arrival of the so-called governments of change. The municipal candidates presented themselves as those with new practices in the way of doing politics, which involved citizen involvement in management through the development of shared information and decision-making spaces, however, it would be false to affirm that they have initiated the participatory public policies in Spain (Mérida & Tellería, 2021).

According to the 2019 Atlas data, the Valencian Community had between 20 and 25% of the Spanish PP experiences, a number that, as can be seen in Table 4, has been maintained after the last municipal elections, although with a small decrease and that they account for almost half of the municipalities studied. This shows that there is a great interest in this community to implement Participatory Budget experiences. It would be interesting to analyze the situation after the next elections in 2023, to find out if the experiences continue despite the entire period of the pandemic.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 4: Municipalities with a Participatory Budget in 2018 and 2020 in the C. Valenciana.

If we take into account the percentage of municipalities governed, as of 2015, by one of the three majority political parties in the community (PSPV, Partido Popular and Compromis) in relation to the number of municipalities analyzed that govern each of the provinces, we see in Graph 2 that in 2018 the two leftist parties (PSPV and Compromis) have greater representation in the province of Alicante and that instead the Popular Party has greater weight in the province of Castellón, which is the smallest of the three provinces .

Graph 2: Percentage of analyzed municipalities governed by each political party in 2018.

Graph 3: Percentage of analyzed municipalities governed by each political party in 2020.

The situation changes after the 2020 elections, recovering in Alicante and Valencia the power that the Popular Party had had for the last twenty years, the PSPV descends in the three provinces and Compromis increases it in all three. Despite these changes, there is not a great variation in the number of PP experiences.

Despite the decrease in the percentage of municipalities governed by the PSPV after the 2019 elections, the population governed by this party did not decrease as much, going from 54.7% in 2015 to 49.7% in 2019. The Popular Party, despite increasing the percentage in the province of Castellón, it fell from 8% to 6.3% of the population. Only Compromis increased its percentage of the population, from 37 to 44%, thanks to the advantage achieved in Alicante and Castellón. Which means that, although the PSPV lost the government of some municipalities, it continues to govern almost 50% of the population of the community.

But these data do not help us to know if there have been changes in municipal governments and if these changes have influenced the maintenance or disappearance of PB experiences. For this , the different political changes produced by an election must be understood and if these changes have influenced the PP.

Table 5 shows the changes produced in the different municipalities analyzed after the 2019 elections, both in the municipalities that had PP and those that did not.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 5: Political party changes after the 2019 municipal elections.

In the municipal votes of May 2019, 59 municipalities of the Valencian Community changed the political sign of their mayors, which represents 34.5% of the municipalities analyzed, with the province of Alicante being where there have been more changes (45.31%) and that of Castellón where less (19%). On the other hand, in those municipalities in which there is a PP experience, there have been fewer changes, only 21% of the total number of municipalities analyzed have changed their political sign. It would be necessary to analyze in depth if the PP has been a factor of continuity for the ruling political party or if the reasons have been other.

Of these changes, the most significant as can be seen in Table 6, since they are left-wing parties to a right-wing party, are those of the Socialist Party of the Valencian Community ( PSPV) and Compromises to the Popular Party. In the case of the change from the PSPV to the Popular Party (14 municipalities), four of the PP experiences have not continued, but two new experiences have been launched. From Compromis to the Popular Party there has only been one change and there the PP experience has been maintained. In the changes between the PSPV and Compromis (3 municipalities) we have appreciated that the experience that existed has been maintained and that they have been created in the municipalities that did not have them. The same has not happened when the municipalities have gone from being governed by Compromis to being governed by the PSPV, since two of the ongoing experiences have ended. This goes to show that the change of political sign of the municipal government does not always imply the elimination of the experience, although it occurs more frequently when it goes from a leftist government to a conservative one. At this point, it would also be interesting to know the reasons for the change in the political sign of the municipal government and how it has influenced both the continuity of the PB process and its objectives and methodology.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 6: Changes in the political sign of municipal governments.

We also wanted to analyze, in order to find out if the political decision to launch or continue a PP experience depended on the political sign of the mayor, those cases in which the same political party remained in the municipal government, but despite this Changes were made after the 2019 elections. We have found ten municipalities that considered PP experiences to be finished and another ten that started them, maintaining the same municipal government party. In the case of the municipalities that terminated the PB experiences after 2019, we have found that most have been due to changes in the person leading the experience, be it the mayor or a councilor. In the case of the councilors, one of them was from the same party as the mayor, although in most cases they were councilors from another party who governed in coalition with the majority party, through a legislature pact, and who did not leave elected at the next election call. Something similar happens when it is decided to launch a PP experience. Other reasons for the end of the process are the difficulty of managing the proposals or the decision that the money that was used for the PB go to a single proposal. In the only case that we have found of the Popular Party, the explanation of the experience is the hiring of a consultant to implement a project-type initiative associated with transparency and open government, a project in which the PP is included.

In order to find out if the decision to launch PP experiences is a global proposal of the political parties or they are isolated proposals of municipal politicians, we have carried out an analysis of the municipal framework programs of the three main political parties with representation in the Valencian Community of the elections of 2015 and 2019, having appreciated that in none of them there is a clear reference to the PP or an application proposal, as if it happened in other previous municipal elections. This does not mean that the PP is not referred to in the specific electoral program of some municipalities, but it does show that the PP is not a general party policy.

Despite this, there are differences between some programs and others. In the PSOE of 2015 there is talk of making public the information related to budget items and in the section on young people it refers to the possibility of sending their proposals to the participatory budgets. In the 2019 report, reference is made to the transparency of public accounts, to the holding of citizen assemblies in which management will be accounted for and complaints, suggestions or contributions will be collected. by the citizens and, there is also talk that the draft of the municipal budgets that will reserve an annual amount for investments that will be decided directly by the neighbors will be submitted to information and debate. in participatory processes, in which the proposals will be selected and voted on, which will finally be taken to the final budget items. The latter, although it does not receive the name of PP, is really a PP.

In the Compromis there is no reference to the PP, but to citizen participation when they refer both to its economic model and to the different public policies. In addition, they point out that they will promote an Open Government Law, which opens the doors of the administration to citizens, encourages their participation in decision-making and guarantees transparency in the management of public money.

In the 2015 Popular Party program there is no reference to the PP or to participation in the budget. Regarding participation, they point out that they will promote the improvement and application of regulatory instruments and citizen participation mechanisms to achieve greater interaction between municipal officials and residents, emphasizing the use of ICTs for this. In 2019 there are no such references, it is a program focused entirely on the economy.

Another issue that we analyze is whether the political decision to launch a PP experience depends on the political sign of the municipal government, whether it is those municipalities governed by left-wing parties that apply these projects the most. As can be seen in graph 4, the largest number of experiences in the two legislatures are found in municipalities governed by the PSPV (58.75% and 53.66%), although after the 2019 elections the number of experiences decreased (10 experiences). The other two parties that have a significant number of experiences are Compromises, which went from 14 to 16 experiences, and the Popular Party, which went from 10 to 19 experiences, which represented a significant increase.

Graph 4: PP experiences by political party in 2018-2020.

As can be seen, there are experiences promoted by both leftist and conservative parties, which demonstrates the ideological heterogeneity of the project. Although most of them occur in municipalities governed by left-wing parties, as can be seen in graph 5, what has happened since the beginning of the implementation of PP experiences in Spain (Pineda, 2010). Without forgetting, furthermore, that it was a left-wing party, Izquierda Unida, which brought the first experiences of PP to the Spanish municipalities, having the city of Córdoba as its main reference.

Graph 5: Number of PP experiences according to ideological orientation.

These data confirm that it is the left-wing parties that mostly launch PP experiences, although there are already parties of another political bias that do so, albeit in a minority.

These data confirm all the hypotheses raised. The first is that all the experiences of the Community are launched in accordance with the political will of the government, be it the mayor or a councillor. Councilor who can be from the majority party or from the minority party in the case of coalition governments. The second is that its implementation is not part of a general policy proposed by any political party, but rather they are individual proposals by elected mayors or councillors. The third is that it is the municipalities governed by political parties with a left-leaning tendency (PSPV or Compromise) that mostly launch PP processes, although more and more municipalities governed by the Popular Party also do so. Finally, it is important to point out that most of the time the experiences disappear when the political sign of the municipal government changes, but it can also occur for other reasons.

Conclusions

All the experiences analyzed in the Valencian Community are born from a political decision of the municipal government, since there is no provision in the Spanish legal system, except for the “Large Cities” Law, any precept that includes the participation of citizens in decision making. budgetary measures, as is the case in other countries such as Peru since 2003, the Dominican Republic since 2007 or South Korea since 2011.

This political decision can be promoted by the mayor or a councillor, which means that it may or may not have the support of the entire government. In the case of some coalition governments, the minority partner is usually the one that promotes the PP project, with the negative consequences for its operation that this situation causes, as the other members of the government feel that it is an imposition. Another negative aspect that is perceived in some experiences is the identification of the process with the party that starts it, which causes a loss of its potential and its disappearance when the political sign of the municipal government changes. To solve this issue, it would be interesting for the government team to involve the opposition in the project.

And although the impulse of the PP responds in all the municipalities to a certain political will, because otherwise they would not be carried out, there is generally little political commitment. It is evident when seeing that this type of experience tends to be residual within the government structures, being in charge, in most cases, of its management the councilor or councilor of citizen participation. In addition, there is usually little involvement of the different departments of the local administration affected by the results of the process, a fact that greatly hinders both the development of the process and the execution of its results.

In the analyzed municipal programs, from the 2015 and 2019 elections, of the three main political parties of the Valencian Community, no specific reference is made to the Participatory Budget. This shows that launching a PP experience is not a global strategy of any political party. However, in the framework program of the PSOE for the municipal elections of 2019 there is talk that the draft of the municipal budgets that will reserve an annual amount for investments that will be decided directly by the neighbors will be submitted to information and debate. in participatory processes, in which they will select and vote on the proposals that will finally be taken to the final budget items. The latter, although it does not receive the name of PP, is really a PP.

Despite not mentioning the participatory budget in any of the programs of the three parties, it is important to point out the differences between the programs of the PS PV and Compromis and that of the Popular Party in terms of citizen participation, in the first two there are clear references to the role that citizens should have in the management and government of the municipalities and in those of the Popular Party there is little mention of the subject and when it is done it has a very normative nature and is related to ICTs. Despite this, the three parties are launching experiences in some of the municipalities they govern.

The data also confirm that the left-wing parties are the ones that mostly launch PP experiences in the Valencian Community (72%), although parties of another political bias also do so, although more minority. Perceiving clear differences in the objectives of the experiences according to the ideology of the municipal government.

It is also observed that those PPs that arise from a political decision based more on a trend or “fashion” than on a conviction about the advantages of citizen participation, that is, they consider it more of a neutral technical tool of good governance more than a political institution ( Wampler & Goldfranck , 2022, p. 12), they tend to use the internet as the only way to participate, using ICT only for collecting proposals, as if it were a mailbox.

The “politicization” of the PP, as we have already pointed out, has both negative and positive aspects. Having political backing can strengthen commitment and ensure adequate resources, but it also creates critical vulnerabilities that can affect long-term sustainability. It has been verified when analyzing the data that the identification of the proposal with a specific political party can ruin its future, some experiences have disappeared not because they did not work well but because when another political party won the following elections it did not want to be related with the project of its predecessors.

The centrality of political will can make a PP process more “vulnerable” compared to other more institutionalized participatory processes. Finding the right balance between all these aspects can be a key success factor in PP processes in all parts of the world.

Finally, note what Yves Cabannes (2004) indicates: “The will has to be maintained throughout the process, but fundamentally it must be specified in the fulfillment of the budgetary commitments contracted with the population” (p. 30). If it doesn’t happen that way, the process tends to create mistrust among citizens and ends up disappearing.

El objetivo de este trabajo es confirmar empíricamente, por medio del análisis de los municipios con Presupuesto Participativo en la Comunidad Valenciana después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y 2019, que la voluntad política es un elemento fundamental para la puesta en marcha y la continuidad de las experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo. La metodología utilizada ha combinado técnicas de investigación social cualitativas y cuantitativas. Los resultados han demostrado que la voluntad política es una variable importante para la puesta en marcha de las experiencias, pero que, para su continuidad, puede ser un problema sino se incorporan otros compromisos. Sin embargo, no es una política global de ningún partido político, aunque la participación ciudadana es una política más integrada en los partidos de la izquierda, siendo estos los que ponen en marcha más experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo.

The objective of this work is to empirically confirm, through the analysis of municipalities with Participatory Budgeting in the Valencian Community after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019, that political will is a fundamental element for the implementation and continuity of Participatory Budgeting experiences. The methodology used combined qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. The results showed that political will is an important variable for the implementation of the experiments, but that its continuity can be a problem if other elements are not incorporated. The OP, however, is not a global policy of any political party, although citizen participation is a strand most found among leftist parties. Thus, these parties are the ones that most initiate Participatory Budgeting experiences.

Referencias

Allegretti, G., García-Leiva, P. & Paño, P. (2011). Viajando por los presupuestos participativos: buenas prácticas, obstáculos y aprendizajes. Ediciones de la Diputación de Málaga (CEDMA).

Avritzer, L. (2009). Participatory institutions in democratic Brazil. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Baiocchi, G. & Ganuza, E. (2014). Participatory budgeting as if emancipation mattered. Politics & Society, 42(1). 29-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329213512978.

Cabannes, Y. (2004). ¿Qué es y cómo se hace el Presupuesto Participativo? 72 respuestas a Preguntas Frecuentes sobre Presupuestos Participativos Municipales. UN-Hábitat.

Cabannes, Y. (2020). Participatory Budgeting contributions to leave no one behind and no place behind: Lessons from the past three decades: Final draft 3. UN Habitat [Working Paper, Unpublished].

Cernadas, A., Pineda, C. & Chao, L. (2013). Democracia Local y Participación Ciudadana. Estudio comparativo de Galicia y La Rioja. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas, 12(1), 175-209.

Dias, N., Henríquez, S. & Simone, J. (Eds.) (2019). Participatory Budgenting World Atlas. [Atlas Mundial de los Presupuestos Participativos]. Epopeia.

Dias, N., Enríquez, S., Cardita, R., Júlio, S. & Serrano, T. (2021). Atlas Mundial dos Orçamentos Participativos 2020 – 2021. Epopeia e Oficina.

Fedozzi, L. (2000). O poder da aldeia: gênese e história do orçamento participativo de Porto Alegre. Tomo Editorial.

Fedozzi, L., Ramos, M. & Gonçalves, F. (2020). Orçamentos Participativos: variáveis explicativas e novos cenários que desafiam a sua implementação, Rev. Sociol. Polit., 28(73), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-987320287305.

Fernández, C. & Pineda, C. (2005). Presupuesto Ciudadano: un análisis sobre el desarrollo de la experiencia de participación presupuestaria en la ciudad de Logroño. Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas, (33-34), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.24965/gapp.v0i33-34

Font, J., Della, D. & Sintomer, Y. (2014). Participatory Democracy in Southern Europe. Rowman and Littlefield.

Galais, C., Corrochano, D. & Fontcuberta, P. (2011). ¿Por qué se ponen en marcha los procesos participativos?. En Democracia local en Andalucía. Experiencias participativas en los municipios andaluces (pp. 35-58). Fundación Pública Andaluza Centro de Estudios Andaluces, Consejería de la Presidencia, Junta de Andalucía.

Goldfrank, B. (2006). Los procesos de “presupuesto participativo” en América Latina: éxito, fracaso y cambio. Revista de Ciencia Política, 26(2), 3-28.

González, A. & Soler, A. (2021). Nuevas miradas de los presupuestos participativos: los resultados de la participación desde la perspectiva política y técnica. OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 16(1), 135-150. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2021.16.1.09.

Holdo, M. (2020). Contestation in Participatory Budgeting: Spaces, Boundaries, and Agency. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(9), 1348-1365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220941226

Horochovski, R. & Clemente, A. (2012). Democracia deliberativa e orçamento público: experiências de participação em Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Recife e Curitiba. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 20(43), 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-44782012000300007.

Lehtonen, P. (2021): Policy on the move: the enabling settings of participation in participatory budgeting, Policy Studies, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2021.1895981.

López, S. & Gil-Jaurena, I. (2021). Transformaciones del Presupuesto Participativo en España: de la aplicación del modelo de Porto Alegre a la instrumentalización de las nuevas experiencias. OBETS, Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 16(1), 151-174. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2021.16.1.10

Lüchmann, L. (2003). Redesenhando as relações sociedade e Estado: o tripé da democracia deliberativa. Katályses, 6(2), 165-178.

Lüchmann, L. (2014). 25 anos de Orçamentos Participativos: algumas reflexões analíticas. Política & Sociedade, 13(28), 167-197. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7984.2014v13n28p167

Mayor, (2016). Presupuesto Participativo de Molina de Segura. Murcia: Ayuntamiento de Molina de Segura.

Mayor, J. (10 de noviembre de 2017). Presupuestos Participativos en la Región de Murcia: una visión crítica [Presentación]. V Congreso Internacional sobre Innovación Tecnológica y Administración Pública. La reforma de la Ley estatal de Transparencia: retos y posibilidades, Toledo.

Mayor, J. & Alarcón, G. (2020). Presupuestos participativos: aspectos conceptuales y previos a su implementación. En: Presupuestos Participativos: aportes y límites para radicalizar la democracia (Pp. 35-57). Tirant lo Blanch.

Mérida, J. & Tellería, I, (2021). ¿Una nueva forma de hacer política? Modos de gobernanza participativa y Ayuntamientos del cambio en España (2015-2019). GAPP, (26), 92-110.

Pineda, C. (2004). Los presupuestos participativos en España: un balance provisional. Revista de Estudios Locales (CUNAL), (78), 64-76.

Pineda, C. (2010). Los presupuestos participativos en España: un nuevo balance. Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, (311), 277-302. https://doi.org/10.24965/reala.v0i311

Pires, R. (2011). Efetividade das instituições participativas no Brasil: estratégias de avaliação, IPEA (7.a ed.). Ipea. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/livros/livro_dialogosdesenvol07.pdf