Analysis of the solid waste containerization activity in Bogotá1

Analysis of the solid waste containerization activity in Bogotá

Abstract

The objective of this research is to contribute to the impact’s analisis of the containerization activity on the collection of usable and non-usable solid waste in Bogotá, integrating the perceptions of citizens and leaders of Trade Recyclers Organizations ORO, as well as information from sanitation operators. The methodology is mixed, in two phases: 1) Quantitatively, the perception of 377 Bogota citizens is analyzed through an online survey; 2) Qualitatively, the opinions of the leaders of fourteen (14) ORO are analyzed through a semi-structured interview. As results, it was found that containerization has structural flaws; a lack of civic culture due to poor awareness and training; the leaders of the OROs indicate that the work of the recyclers has been harmed and that the goals of recovering at least 50% of the waste that arrives at the Doña Juana landfill, as proposed by the UAESP, are not being met.

Key words:

waste, containerization, source separation, recycling..Resumen

El objetivo de la presente investigación es aportar al análisis del impacto de la actividad de contenerización para la recolección de residuos sólidos aprovechables y no aprovechables en Bogotá, integrando las percepciones ciudadanas y de líderes de Organizaciones de Recicladores de Oficio ORO, así como información de los operadores de aseo. La metodología es mixta, en dos fases: 1) Desde el enfoque cuantitativo se analiza la percepción de 377 bogotanos a través de una encuesta en línea; 2) Desde el enfoque cualitativo se analizan las opiniones de los líderes de catorce (14) ORO, por medio de la entrevista semiestructurada. Como resultados se encontró que la contenerización presenta falencias estructurales; falta cultura ciudadana por la escasa sensibilización y capacitación; los líderes de las ORO indican que la labor de los recicladores se ha visto perjudicada y que no se están cumpliendo las metas de recuperar por lo menos el 50 % de los residuos que llegan al relleno sanitario Doña Juana tal como lo propone la Unidad Administrativa Especial de Servicios Públicos - UAESP.

Palabras clave:

residuos, contenerización, separación en fuente, reciclaje..Introduction

The efficient management of solid waste is one of the tasks that different cities at the national and international levels have been working on in order to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG11 and SDG12), on sustainable cities; and responsible production and consumption. Bogotá has not been immune to these dynamics and has established a cleaning scheme focused, among other aspects, on improving the use of solid waste, through different activities, including containerization.

The Free University from the Organizations and Society Management Group and the Surcolombiana University from the Iguaque Group, supported by the Thematic Network on Comprehensive Solid Waste Management of the Colombian Environmental Training Network, joined forces, and set out as the objective of this research to analyze the containerization activity for the collection of usable and non-usable solid waste in Bogotá.

Methodologically, the study applies a mixed research approach, which starts from the perceptions of citizens and the Professional Recyclers Organizations, hereinafter GOLD; and the bet of the District Administration on the activity of containerization, which seeks to improve the quality in the provision of the collection service, from three fundamental aspects: keep the spaces clean; promote source separation; avoid the appearance of critical points (foci of contamination). From there, the question posed for the study is what is the perception of citizens and professional recyclers about the impact of the containerization activity aimed at the collection of usable and non-usable solid waste in Bogotá?

This article is divided into nine parts, the first being this introduction. Beginning with the referents, from the second to the sixth part, the context of waste containerization in Bogotá DC is analyzed, as in other countries; likewise, the final destination of the city’s ordinary and recyclable solid waste, and the regulatory framework for solid waste management in Colombia. The seventh part explains the methodology used. The results are presented in the eighth part, to end with the conclusions of the investigation.

Context of waste containerization in Bogotá D.C

Based on the information provided by the UAESP and the Aseo consortia, requested ex officio from the generators of this study, it was possible to identify the current context of the containerization strategy in Bogotá. Thus, within the framework of the development plan of the last District Administration of Bogotá (2016-2019) in the goals on the vision of the city, it was proposed to deliver in 2020 a capital city where “a recycling model with better use of waste, rubble and garbage” (Mayor’s Office of Bogotá, 2016, pp. 66-67). To achieve this goal, the Special Administrative Unit for Public Services UAESP, in charge of the implementation and compliance with the sanitation and garbage collection scheme in Bogotá, proposed the installation of containers by the sanitation operators, for the activity of solid waste collection in the city of Bogotá DC (LIME, 2021; UAESP, 2021a; Clean City, 2021; Promoambiental District, 2021; Bogotá Clean, 2021).

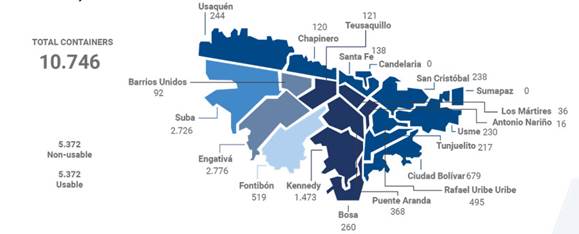

The new waste collection scheme proposed by the Mayor’s Office (Figure 1) had as an environmental goal the installation of containers and garbage cans throughout the city to recover at least 50% of all usable waste that goes to the Doña Sanitary landfill. Juana (CJS Canecas, 2019). In the same way, the main objective determined by the UAESP in the installation of the containers for the collection of solid waste was “to mitigate the environmental effects and avoid the generation of vectors and spread of waste, as well as the appearance of sources of contamination, that affect and deteriorate the harmony of the urban public space” (UAESP, 2017, p. 4).

Figure 1: Containers installed in Bogotá

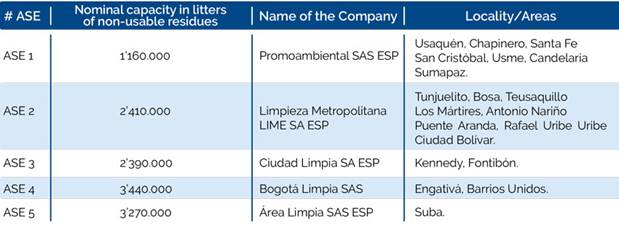

According to the UAESP (2018) “containerization is a great step to modernize the provision of the sanitation service in Bogotá since it allows improving the presentation of waste, avoiding its accumulation and promoting recycling” (para. 5). As part of the concession contract that started the new cleaning and waste collection scheme in Bogotá in 2018, for a total value of 4.8 billion pesos and with a validity of 8 years with each of the operators of winning toilets (Cuevas, 2018), the exclusive service areas (ASE) were assigned, divided as shown in Table 1:

Source: taken from UAESP (2017).

Table 1: Areas in Bogotá

With the award of the respective contracts, powers and responsibilities were granted to each of these operators, where one of their new objectives included the installation, cleaning and maintenance of the containers located throughout the city; as well as their respective pedagogy and social awareness with recyclers by trade and citizenship in general, since one of the most outstanding advantages would be, according to Cuevas (2018), “certain and safe access to usable material: Recyclers will be the only ones authorized to carry out the collection and use of usable material, in accordance with the routes and associations corresponding to each ASE” (Párr. 15).

A total of 10,746 containers are in the city, 5,373 for non-usable material and 5,373 for usable material. They were distributed using the division through the Exclusive Service Areas (ASE), considering the places where a higher concentration of waste originates (UAESP, 2021b, p. 3) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Container location by ASE.

Context of waste containerization in other countries

References can be found in the world of the toilet model accepted in Bogotá, made up of containers for the collection of both usable and non-usable waste. For example, the European continent has implemented cleaning schemes in proportion to the usable material that is recovered from the waste. Spain separates waste for recycling through colored containers located throughout the public space; For the year 2016, Spain had 33.9% of recovered usable waste, translated into 1.3 million tons of usable waste (Ecoembes, 2021), although significant, far from the 55% required by the European Union for 2025 (Benito, 2020).

Germany and Belgium stand out in their models of recovery of usable waste, through colored containers, they use a system of taxes on recycling and the use of official bags to deposit waste, managing to occupy the first places in recovery of usable material with a 65% and 55%, respectively (Calero, 2018).

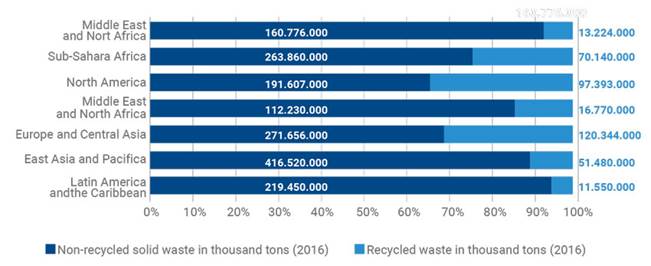

While the European region is at the top of the best waste management practices, where more than 200 cities exceed 50% recycling (Montes, 2019), Latin America shows a lack of culture and commitment in waste management and government measures that allow the recovery of a considerable amount of what is discarded by the population. This is how the data from the World Bank (2018) indicate that in Latin America the annual production of waste is 219,450,000T and only 11,500,000T are recovered (see Figure 5).

There are very few countries that have implemented in their waste management scheme the installation of containers in public spaces for the separation of waste, one of these cases is found in Chile, which through its green points (spaces with containers installed to dispose of waste) accessible to the community, establishes the colors of the containers to identify the different types of waste, based on the Chilean Standard NCH 3322:2013 of the National Institute for Standardization (Ministry of the Environment, 2021); In 2019, before the pandemic, a total of 7,186 green point containers were recorded throughout the country with a monthly reception capacity of 12,890 tons of cardboard, paper, plastic, glass, metal, cell phones and batteries (País Circular, 2019).

Impacts of solid waste in cities

Gábor & Aguilar (2006), Espinosa & Castrillón (2013) and the World Bank (2018), agree in affirming that the environmental impact of solid waste goes beyond the production or generation of the same in situ , since the management that is gives to these and the final disposal generate negative impacts both on the soil and water (generation of leachate), as well as on the air (visual pollution and odors), biodiversity (focus of generation of vectors and pathogens) and in general the quality of life of humans and non-humans (they affect the landscape, they are a means of spreading diseases, among others).

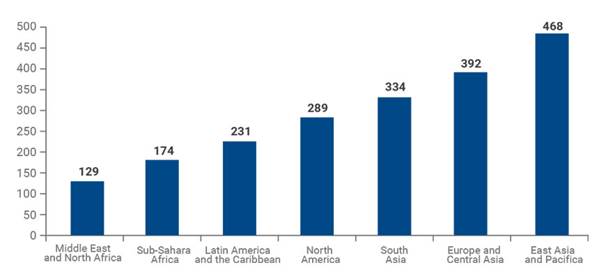

Regarding the production of waste worldwide and by region, the World Bank report (2018) estimated that the global generation of waste in 2016 reached 2010 million tons of municipal solid waste. By the year 2030 it is expected that the world will generate 2.59 billion tons of waste and if the pertinent measures are not taken, global waste will increase by 70%, that is, 3.4 billion tons would be generated by the year 2050 (World Bank, 2018. p.18) figures that contradict the goals of the 2030 Agenda (ECLAC, 2018) in SDG11 “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” and SDG12 “Ensure modalities of sustainable consumption and production” (Para. 1), targets 11.6 and 12.5, on the need to significantly reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse.

As shown in Figure 3, the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa regions generate the least waste with 129 and 174 million tons representing 6% and 9% respectively of total waste. in the world as of 2016. Latin America and the Caribbean ranks third with 231 million tons representing 11% and the East Asia and Pacific region generates the largest amount of waste with 468 million tons equivalent to 23% in that same year.

Figure 3: Waste generation by region in million tons

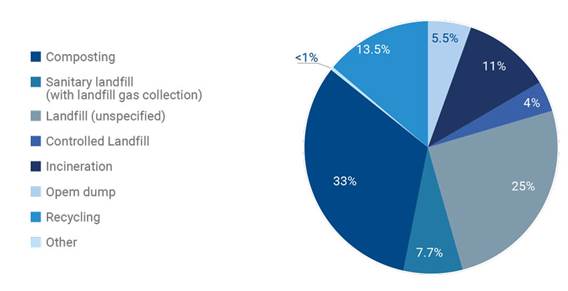

In relation to the disposal of solid waste, it is worrying that worldwide 33% of waste has inadequate management processes where it is dumped on roads, open land, or river sources. Almost 37% of the waste in the world is disposed of in landfills of all kinds, as shown in Figure 4. Around 19% is recovered through recycling and composting processes and 11% of the waste is treated through incineration (World Bank, 2018, p. 34).

Figure 4: Global Waste Treatment and Disposal in Percentage.

The regions with the highest income such as North America and Europe have the highest amount of waste recovery through recycling and composting in 2016. The regions with the lowest amount of waste recovered in the world are Africa Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean as shown in Figure 5 (World Bank, 2018, p. 35).

Figure 5: Amount of non-recycled and recycled waste in the world.

In Colombia, according to data from Semana (2020), only 17% of its solid waste of the almost 12 million tons generated annually is recycled, establishing a modest goal of achieving 40% of recyclable material by the year 2030. Bogotá, despite being the city in the country with the highest proportion of households that report having waste classification habits with 62% of the total, according to Malaver (2021), only 16%, equivalent to 1,200 tons of waste, can be recovered and used. the 7,500 tons of waste generated per day.

The destination of the city’s ordinary and recyclable solid waste

The landfill is one of the most used technologies in Colombia for the final destination of solid waste, however, it is an obsolete technology, since the trend should be the growth of circular economy processes together with professional recyclers, to reduce minimize the waste of raw materials and reincorporate solid waste into the production chain, from a cradle-to-cradle perspective, and not from the cradle to the grave. In other words, return waste in such a state that nature can reabsorb it and that it does not contaminate the soil, water sources, the air and biodiversity, as well as human health.

In the particular case of Bogotá, there is the Doña Juana Sanitary Landfill, which daily receives around 6,500 tons of ordinary waste, of which 80% could be used, but ends up underground causing pollution (Vargas, 2021). Thanks to the work of more than 22,000 recyclers by trade and some families and citizens who carry out separation at the source, 1,200 tons are recovered in the city, which according to data from the Bogota Environmental Observatory (2022), is equivalent to 16% of the total waste generated in the city; that is to say, a total of between 7,500 and 7,700 tons of waste are produced in Bogotá, material that comes, on the one hand, from the containers located in the city, but on the other hand, from the routes that recyclers make through the city in residential complexes, companies, educational institutions, among others.

According to the most recent report published on the achievements of the Mayor’s Development Plan “A new social and environmental contract for the Bogotá of the 21st century” 2020-2024, by the year 2020, 1,300,116 tons of waste were used, thanks to recyclers’ organizations and what is reported in the Single Information System for Public Services SUI. The report highlighted that with the exploitation model implemented in the city, an increase from 18% to 24% of the material that has been recovered has been observed (UAESP, 2021c, p. 2).

Much of this recoverable waste is directed to the transformation processes through the Recycling Organizations, defined by Resolution 61 of 2013 of the UAESP, as one:

“non-profit entity constituted mainly by trade recyclers, whose corporate purpose is related to the provision of the public cleaning service in the components of use and recycling, with a high degree of empowerment and representativeness in the operational, administrative and management processes. decision-making by its associates” (p. 10).

Most of these associations rent warehouses for storage and seek to establish alliances with material transformation companies to reduce intermediation; These alliances include ANDI (National Association of Entrepreneurs) and CEMPRE (Business Commitment to Recycling).

In 2006, the Mayor’s Office, through the Comprehensive Master Plan for Solid Waste (Decree 312 of 2006), set out to create parks or recycling plants in some of the towns of Bogotá (Mayor’s Office of Bogotá, 2012). An example of this is the La Alquería Recycling Center, which was assigned thanks to ruling T724 of 2003 of the Constitutional Court, on the obligation to generate affirmative actions in favor of the recycling population of Bogotá in a state of poverty and vulnerability, the which, according to Parra Deputy Director of Use of the Administrative Unit of Public Services UAESP, is not enabled, since in December 2019 it suffered a fire that affected the entire area where the use activity was carried out by the ORO included in the Single Register of Trade Recyclers Organizations -RUOR- that operated in this place.

The situation described above is unfortunate, because in addition to its function of taking advantage of the material recovered in the streets of Bogotá by the recyclers, in the Alquería the recyclers were trained and the organization of educational visits was allowed, where the citizens could know the plant and each one of the processes of separation, classification, storage and commercialization of the usable material; Similarly, it promoted environmental education on separation at the source and the correct management of waste, reducing its impact on the environment (Alcaldía de Bogotá, 2012).

In relation to the recycling plants for Bogotá, the construction of 6 more plants was planned, whose purpose was the use and commercialization of recyclable waste such as paper, cardboard, plastic, metal and glass. However, according to El Tiempo (2008), the communities of some of the construction zones were adamantly opposed, preventing the works from starting, alleging that these would generate insecurity and garbage problems in the sector. This situation continues to date (2022) avoiding strengthening the recycling system in the city.

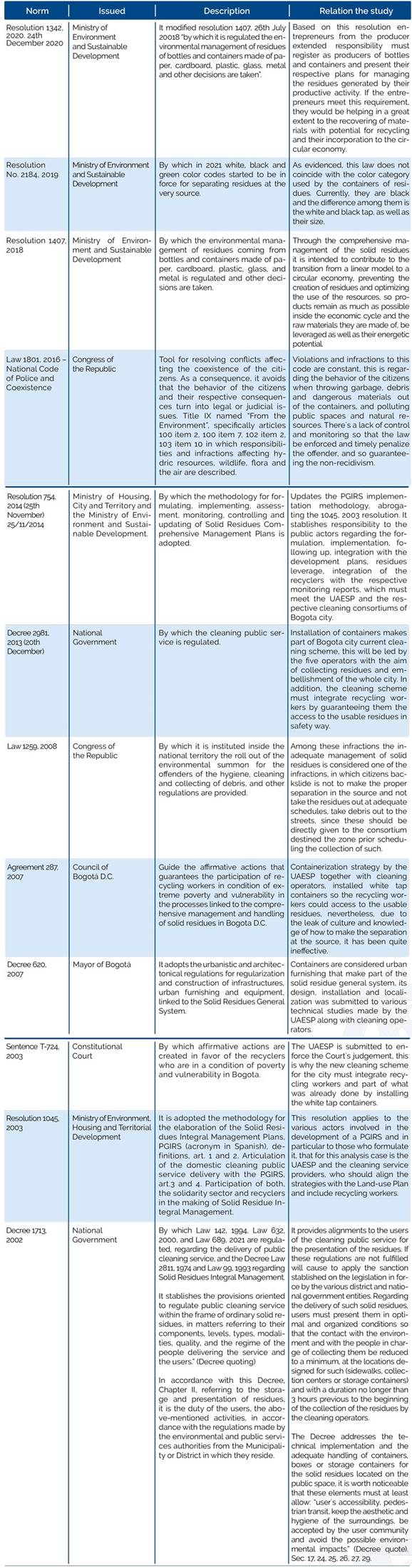

Regulatory framework for solid waste management in Colombia

In Colombia, various laws or regulations have been created and regulated in response to the environmental and health needs of society regarding the management of natural resources and their subsequent waste, with the aim of preventing and mitigating the different problems generated by the incorrect management of waste. these. Table 2 mentions some of the current regulations in Colombia that are related to the proper.

Source: own elaboration based on normative information obtained through different documentary sources.

Table 2: Colombian regulations on waste associated with research

Methodological note

The research approach of the present study is of a mixed type, since it integrates into its analysis both quantitative elements, for the analysis of the surveys applied to citizens, and qualitative, for the documentary understanding and the information obtained from the surveys. applied interviews with the ORO. Using this approach, on the one hand, the situation of waste management in Bogotá is interpreted in what must do specifically with the containerization implemented in the city; and, on the other hand, the information provided by citizens and recycler organizations based on their perceptions and interactions with waste is collected and analyzed.

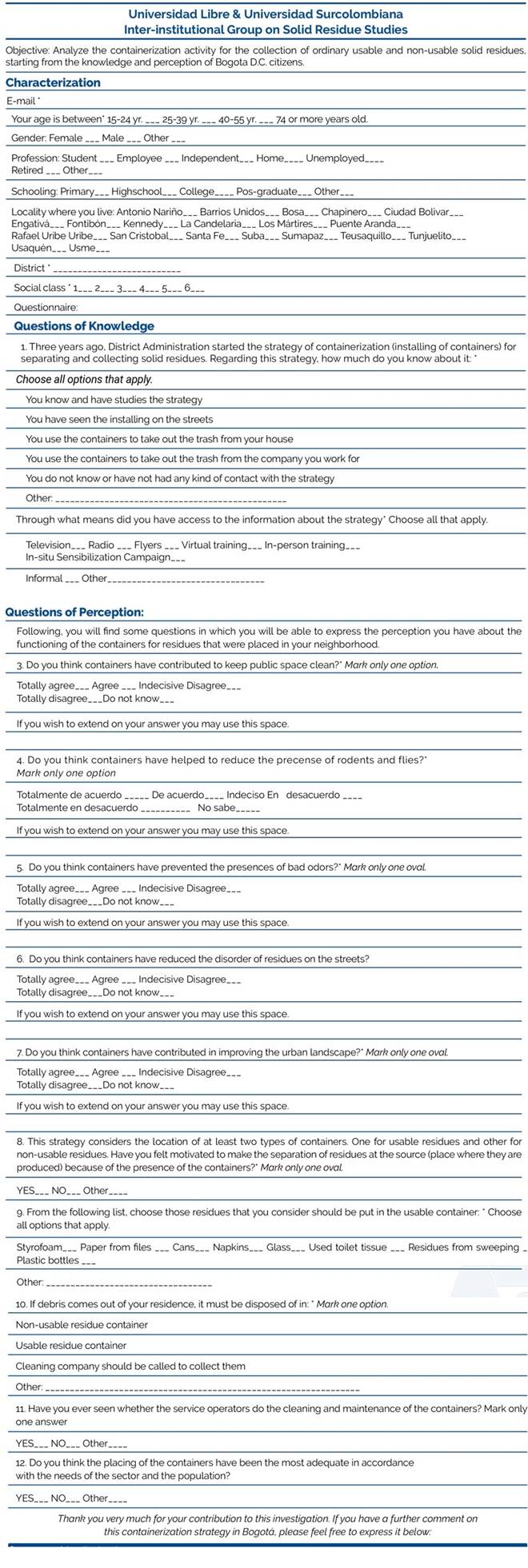

The research is carried out in two phases. In the first, the perception of 377 citizens of Bogotá is analyzed through a survey applied online using the Google platform. The number of citizens surveyed is based on a convenience sample, which is based on the definitions provided by Question Pro (2022), that is, it is a non-probabilistic and non-random sample, based on ease of access and availability of information. people through social networks Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, university email databases, and university networks, in a time interval limited to 20 days, between September 30 and October 21, 2021. This The technique was considered appropriate considering that any citizen from the age of 15 onwards is an eligible participant. The data obtained were analyzed supported by descriptive statistics. The survey (Table 3) is structured in three parts: characterization of the respondents, knowledge, and perception about the containerization activity. In the characterization, the participants are asked for general data such as e-mail, age, gender, dedication, or occupation, among others. In the next section, it asks about people’s knowledge about the containerization activity.

Source: own elaboration (2021)

Table 3: Survey addressed to citizens of Bogotá.

In the perception part, 5 Likert scale questions were used (totally agree, agree, undecided, disagree, totally disagree, or don’t know). In this type of question, it was allowed to expand the answer with additional comments; Likewise, 3 dichotomous questions and 2 multiple-choice questions were included. For the analysis of the results of this section, the opinions of all the respondents were considered, regardless of their level of knowledge about this activity.

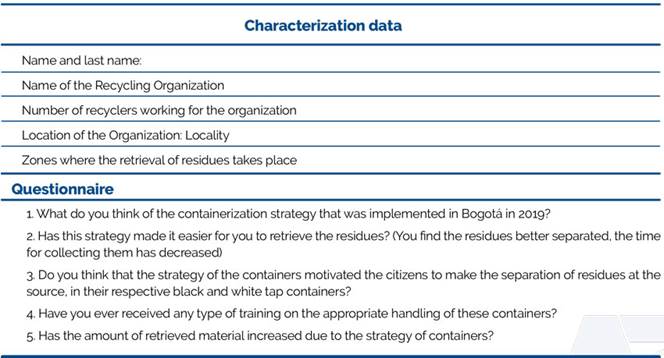

In the second phase, the opinion of the leaders of the professional recyclers’ organizations is investigated. Table 4 presents the instrument used for the semi-structured interview. This instrument has 2 parts, the first related to the characterization of the organization and, the second, the questionnaire regarding the opinion of the leaders of the organizations on the containerization activity.

Source: own elaboration (2022).

Table 4: Semi-structured interview addressed to waste picker organizations.

The population of waste picker organizations identified in Bogotá is 318, based on data provided by UAESP, Superservicios, CRA (2021). Using the entirety of this database, you are invited by email to a virtual interview. Given the isolation conditions of the pandemic generated by COVID-19, between November 2021 and February 2022, and knowing the limited conditions of accessibility to technology, the response of at least 10% of the organizations was expected. However, 14 associations (4.4%) responded effectively to the interview, in which 1705 recyclers are affiliated, of which 1206 are formally associated and 499 informally, who carry out their work in 11 localities.

The criteria of representativeness and empowerment were the main reasons that led this study to seek an approach to these organizations. For this reason, organizations located in 11 locations in Bogotá or with coverage of recycling processes in these were interviewed: Engativá, Tunjuelito, Kennedy, Los Mártires, Bosa, Suba, Fontibón, Puente Aranda, Rafael Uribe Uribe.

Results

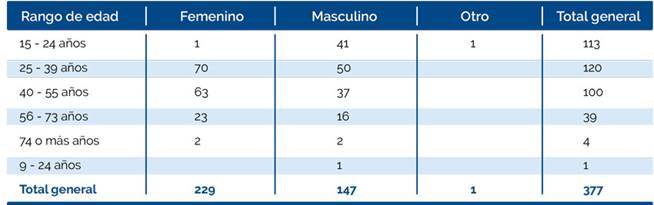

For the development of phase 1, 377 surveys were carried out, of which 60.8% correspond to the female gender. Table 5 shows the total number of respondents by age range and gender. It is observed that 61.8% of the respondents are in an age range between 15 and 39 years old and only 11.4% are 56 years old or older.

Source: own elaboration (2022).

Table 5: Respondents classifled by gender and age

32.9% of those surveyed are students, 41.4% are employed, 15.9% work as independent workers and 9.8% are engaged in housework, are pensioners or are unemployed. Regarding schooling, 45.4% are university graduates, 35.5% have a postgraduate degree, while for 11.6% their level of schooling is secondary and for 7.5% technical, technologist or primary level.

Regarding the knowledge of those surveyed about the containerization activity, 10.6% claim to know and have studied the strategy. While 13.5% do not know it or have not had any type of contact with it. However, all those surveyed gave their opinion about the way this activity works in the city. Of the total, only 109 respondents, that is, 28.9%, state that they use the containers to dispose of the waste from their home and/or from the company where they work.

The foregoing can be explained because not all users make use of the containers, since in some sectors of the city containers were not available and the condominium complexes have their own collection centers. In the words of one respondent “we separate them into colored bags and throw them into a garbage dump, I don’t know if they divide them by container from there”, showing the indifference on the part of users with respect to waste management. solids.

Of those surveyed, 42.2% had access to information about the strategy through television; 10.3% with awareness campaigns on informal sites; 4.8% attended face-to-face or virtual campaigns; 4.2% accessed information through the radio or flyers; and 15.7% saw the containers on the street, used common sense or read the labels on them.

These results (4.8% and 4.2%) show the ineffectiveness of awareness campaigns by the UAESP and the operators of the collection and final disposal service in the different areas of the city. It should be noted that, according to information provided by the sanitation consortia, different campaigns have been carried out in the city in Kennedy and Fontibón by the operator Ciudad Limpia in the month of February 2019; the Clean Area cleaning company in Suba in July 2021; Bogotá Clean has also been carried out in the town of Engativá between 2018 and 2021; Likewise, between 2018 and 2020, Promoambiental Distrito raised awareness among 17,612 inhabitants belonging to the towns of Chapinero, Santa Fe, Usaquén, Usme, La Candelaria and San Cristóbal, just to name a few (Proambiental Distrito, 2021).

To analyze the perception of the respondents about whether the containers have reduced the waste mess in the street, 32% (121 people) agree or totally agree. In contrast, 39.2% disagree or strongly disagree, while 28.8% are undecided or don’t know.

Among the voices of those surveyed, there are those who affirm that the containers “increase the perception of cleanliness and improve efficiency in waste control”; that “although the strategy is very good, not many people have used it correctly, meaning that it does not take full advantage of it” and that “although it is a good strategy, these containers are searched by recyclers and people on the street for that leave the waste scattered around the container”.

However, another respondent states that “sometimes the containers are full, [and] they are not collected in a timely manner and in addition to this, when there is no more garbage, they begin to put it on the sides, which generates a bad smell and makes them not look clean. the streets”, in addition, “many people take out the garbage at the wrong time and they accumulate garbage around it” and “the containers have been put to a terrible use, generating more garbage instead of less”. These expressions show the lack of culture on the part of the citizens.

Regarding whether the containers have helped reduce the appearance of rodents and flies, 143 respondents (38%) agree or strongly agree. Likewise, 33% disagree or totally disagree and 113 people, that is, 30%, are undecided or do not know. When performing the analysis by localities, 8 of the 20 present an average of agreement and total agreement above 38%, being the localities of Barrios Unidos (53.8%), Ciudad Bolívar (44.4%) where the highest Percentage of respondents consider that containers have reduced vectors.

However, those who consider that they do not agree with respect to the reduction of rodents and flies are of the opinion that: when doing their job, the professional recyclers leave waste scattered around the containers; also that the garbage overflows; the containers do not receive maintenance and cleaning; and there is a lack of citizen culture when misusing them, indicating that “citizen duties regarding collection and cleaning are not fulfilled” affirms one of the respondents. The localities where the respondents disagree or totally disagree with the container issue are Kennedy (55.5%), Puente Aranda (44.4%) and Fontibón (39.3%).

In light of the data, the opinion on whether the containers have prevented the presence of bad odors and reduced the mess of waste on the street is divided between those who agree and those who disagree with 38.1% respectively, while 23.7% are undecided or do not know; aspect that deserves further investigation, because it is assumed that the container policy should influence a greater favorable opinion on the improvement of these pollution situations.

The voices of some respondents highlight that the smell of the containers is very strong, since some of them have had their lids removed. In addition, the respondents affirm that there is no adequate maintenance, monitoring, and cleaning of the containers; that when they are full, the accumulation of waste without separation generates bad odours; there are people who leave bags next to it, which increases the mess and the bad smell; those who live near the containers say they put up with the bad smells.

It should be noted that other respondents insist that there is not enough information or awareness among users of the proper handling and care that must be taken with said containers and with the site prepared for it. Likewise, recyclers and homeless people have easy access to the interior of the containers, take the garbage out into the street and spread it, generating bad odors. Some citizens point out that when it is very hot the odors are complex, but to a lesser extent than when they were in the street and collection points were made in disorder.

42.4% of those surveyed consider that containers have not contributed to improving the urban landscape, while 21.4% are undecided on the subject. On the contrary, 36% state that this containerization helps to organize the waste disposed of in the street. In this sense, a respondent affirms that “the areas where there are them look much cleaner and do not hinder or obstruct vitally”.

Regarding the question of whether they have felt encouraged to separate waste at the source (place where it is produced) with the presence of containers, 55.7% of those surveyed say no, while 44.3% say yes. Among the arguments for not feeling incentivized are that they already did the separation at the source before the containers were placed, they already participated in environmental initiatives, or they do not feel stimulated to do separation because they observe that all the waste is put in the same truck. of garbage. In this sense, one of the respondent’s states: “I already do it, but I don’t see that the collection companies, recyclers and homeless people don’t make proper use of them, and some [containers] are already damaged and the people deposit without discriminating.”

Within the survey, two verification questions were asked about the knowledge of the respondents about those residues that they consider should be placed in the reusable container. It is found that Styrofoam, used toilet paper, sweeping waste and napkins are considered usable waste, which shows the lack of knowledge and citizen culture on the subject. The opposite occurs with the disposal of debris, since only 18% do not know how to dispose of this type of waste. The knowledge in this regard by the respondents who live in Ciudad Bolívar stands out, since 94.4% know the proper management of these wastes.

Regarding the operation related to the activity of containers, the survey included two questions: the first, related to the observation by the respondents about whether the service operators perform cleaning and maintenance of the containers; the second: on whether the location of the containers has been the most appropriate according to the needs of the sector and the population.

In the case of the first question, it is found that 77.4% of the respondents do not observe that the containers are washed or fixed. However, the operator LIME (2021) indicates that to date it has 2 container washing vehicles to clean 2,302 of these, located in the towns of Antonio Nariño, Bosa, Ciudad Bolívar, Los Mártires, Puente Aranda, Rafael Uribe Uribe, Teusaquillo and Tunjuelito. Regarding the second question, despite the technical studies that the different operators present to justify the location of the containers, 55.4% of those surveyed think that it has not been the most appropriate, for them in some places they are needed, and in others there are too many or are far away for users.

Regarding the results of the second phase of the study, to recognize the perceptions of the recyclers by trade, 14 interviews were conducted with leaders of recycler organizations whose objective was to know the perceptions regarding the containerization strategy for waste collection implemented in Bogota since 2019.

The first question was focused on knowing in a general way the perception of the leaders of the recycler organizations about the containerization strategy, in this regard responses were identified in favor of the strategy (3) and against (11), with various arguments for justify their answers.

Those who expressed being in favor expressed that the strategy is good for recyclers since now they do not have to go from house to house, however, against the strategy they express that collection is frustrated because people do not separate waste at home and now the recyclers have to get inside the containers to recover the potentially recyclable materials, arguing that the main causes have been the lack of dissemination on the proper use of the containers and the lack of training for users on the processes of separating waste. waste at the source.

This shows that both the respondents and the interviewees agree that one of the main weaknesses of the waste containerization activity in the city is related to the lack of culture on the part of the people and of processes of sensitivity and training for citizens.

The leaders of the recyclers who express explicit rejection, for the activity, consider that it has been negative with expressions such as “it has been the worst invention that the District has created” (Arana, 2021), explaining that, on the one hand, containerization ended garbage day, that is, previously every third day the waste was delivered to the company, now people take out the waste at any time, therefore, the recyclers must pass all the days to make the collection in the multiple containers as indicated by ASCOREH (2022):

“It affected us too much, the organized trade recyclers who comply with many parameters required by the government because before placing them, people had a schedule to take out the garbage and we had the time to recycle, take out all the usable material now with those containers people take out your garbage at any time, any day and now”.

They also point out that this fact generates more contamination for the community due to the permanent presence of waste in the street, since people do not always place the bags inside the containers, and many recyclers when recovering the materials, break the bags and leave the waste outside of them. Similarly, the containers expel bad odors, which affect the community. This problem was also explicitly expressed by the citizens surveyed.

In the same way of rejecting the strategy, they point out aspects such as “there are flaws in the containers, because they do not meet the appropriate conditions for recyclers to operate them and recover the material” EMR (2021), “They were not installed on routes that benefit the recyclers, if not with the criteria of the sanitation operator and there are currently many damaged containers”. “The size of the containers makes it difficult to recover usable waste”, “there is no culture at the time of disposing of waste, they did not meet the goal that they wanted to achieve, which was to greatly facilitate the issue of recycling, and therefore on the contrary, the recycler has been harmed”, “Technically the strategy is good, because it should help the population to become aware, and have good waste management for recyclers, but in practice it has been a disaster” ACORVE (2021).

Some of the answers presented by the leaders of the associations in the previous question, are related in this section, with the second question asked about whether the strategy has facilitated the waste recovery process? Here it was sought to identify if, because of the implementation of the containers, the waste is better separated, or if the collection time has been reduced. Regarding this specific aspect, they point out that almost the same amount of time is spent, because, although now the waste is concentrated in the containers, the users do not adequately separate the waste, which means that the recyclers must get inside the containers, to be able to recover the materials. On the other hand, they highlight the high risk of this work because they find sharp things, hazardous waste mixed with potentially recyclable waste, bad smells, among others. They also indicate that the containers have become a disadvantage for the work of recyclers because amounts of debris and all kinds of dangerous materials arrive there.

As indicated in the previous question, in relation to the size of the containers, they consider that these have become an impediment to the work of recyclers due to their size, since in this profession there are people of all ages, and especially, elderly recycling population. This last data is consistent with the information obtained in the UAESP’s Characterization Report of the Recycling Population 2020 (2021a), where it is indicated that 24,310 recyclers are registered in Bogotá and of these the elderly population is 17.05%. say 4,143 people. And this is only speaking of those who are registered, since the OROs point out that a high percentage of people who carry out recycling processes are not officially registered and licensed before the district, for example, of the 1,705 recyclers linked to the 14 OROs that provided data to the present study, 29.3% is not formally affiliated with the organization.

Another situation pointed out in relation to aspects that become impediments to making the respective use of the waste, by two of the organizations, is that the homeless go to sleep between the containers, a situation that generates conflicts, since the recyclers take risks for these people to threaten their integrity.

An additional problem considered by the leaders of the associations is the high competition that has been generated between the migrants and the recyclers of the city, the latter have been fighting for years to claim their rights: to work, to dignity, to health, to training, among others, in the words of one of the organizations.

“I do not agree that Venezuelans appropriate the recycling business due to the needs of many Colombians, [who] have been working for many years to acquire certain rights and it does not seem to me that others benefit, while the same fellow citizens they are harmed” (ACORAS, 2021).

In the third question about whether the container strategy encouraged citizens to separate waste at the source in containers with black lids and white lids, the 14 organizations interviewed indicate that the strategy has not been effective, that people It does not have the culture, nor the information and therefore they stir up all the waste. They also insist that people have not received adequate training from the media, nor from the competent authorities, however 3 of the organizations indicate that they themselves have campaigned to promote the separation of waste in the font.

In the words of the ORO representatives, regarding question 3, they state the following: “The community deposits all kinds of ordinary and recyclable debris in the containers. The container became a critical point”, “the culture, tolerance and empathy on the part of the people are not seen since we recyclers put our hands in the garbage without thinking that the waste that is in the containers is not what other unusable and even dangerous waste is expected and is even dangerous”, “The material is contaminated, people do not separate it, they do not care if it is in the recyclable or garbage bin, even dead animals have been found” (GAIAREC, 2021).

With the above, it shows that Law 1259 of 2008 item 7 is violated on the infraction of “Improperly disposing of dead animals, parts of these and biological waste within domestic waste” which indicates that a natural person will be fined 10 SMDLV and a legal person with 10 SMDLV, however, the containerization activity does not facilitate control over who disposes of this type of waste in an inappropriate manner.

“The strategy rather encourages citizens to be untidier, [they take out] the garbage at any time knowing that those containers are there at any time, where they can take out the garbage, and if they are full, easy, they throw the garbage away. outside the container, and more spills” (RASA, 2021).

In relation to the fourth question about whether they have received any type of training for the proper handling of waste containers, the OROs point out in unison that they have not received training, however, they indicate that the same associations that were born to dignify the work of the recycler, are those who train recyclers; In this regard, they point out that “the awareness campaigns that are regulated in annex 2 of the tender regarding training the recycler and giving recognition to the community, this has not been fulfilled by the sanitation operators” (EMR, 2021).

The fifth question, on whether the container strategy has increased the amount of recovered material, there is no general agreement, 3 associations indicate that it has increased, 7 associations indicate that it has decreased, 1 indicates that it is very relative, and 1 that it is not you can know the data accurately. Some extensions on said information say that it is difficult to measure, sometimes it goes up and down depending on the activities in the sector. Sometimes the recyclers do not respect the routes and many people arrive in the same sector. They also indicate that in the pandemic the amount of recoverable waste was reduced, since consumption patterns also changed and much more disposable or non-recoverable garbage was produced; In the words of one of the leaders, “It has not increased, on the contrary, it has decreased and has contributed to generating critical points in the city where rubble, wood and special or dangerous materials are left”, “currently the quantity has increased, not the same than before 2019 but it has improved again this year 2021” (GAIAREC, 2021).

The leaders of the ORO come close to proposing solutions, for example: “It would be important to implement an environmental subpoena to force users to carry out the separation process, because people do it if they want to and if they don’t, they don’t.” However, it should be remembered that since 2008 with Law 1259 “the application of the environmental subpoena to offenders of the cleaning, cleaning and debris collection regulations is established in the national territory” (para. 1) according to this Law, a person who violates the standard of waste separation at the source without considering that each container is suitable for some specific waste, will have a fine of 5 SMDLV when it is a natural person and 5 SMDLV when it is a legal entity, a situation that is the same as in the previous case there is no real sanction for lack of follow-up.

“The use of the black bag and the white bag worked at one time.” “There is no motivation for people, for example, in the cleaning fee for those who recycle: fee reduction.” “Associations in some areas encourage residents by delivering white bags and these bags are collected only with recyclable material” (ANRT, 2021).

They also point out, “we have spoken with the District reflecting the problem, but since it is a contractual matter, there is not much to do legally, we have to wait for the tender to end in order to exercise a strategy of mass education and solidarity delivery to the recycler” (GAIAREC, 2021).

As noted above, the contract is valid for 8 years, beginning in January 2018 and ending in January 2026, however, more than 3 years after the installation of the 10,746 containers on the platforms of the city of Bogotá ( UAESP, 2021b), the UAESP through the sanitation operators, began the installation of a new type of containers, called “underground”, that is, underground, “which have state-of-the-art technology and that will allow optimizing the service that it is offered to citizens”, as mentioned by the General Manager of Clean Area (Editorial Nation, 2022).

This questions the OROs, because in addition to including changes within the validity of the previous contract, they wonder again about the benefits for recyclers, since it is not understood how they are included in the strategy, even despite the State No T ruling. -724 of 2003, where it was indicated that all contracting processes for public cleaning and waste management services in Bogotá must include affirmative actions in favor of recyclers by trade and that for no reason can they repeat omissions as has been done in the past.

As pointed out by Redacción Nación (2022):

“Only non-recyclable waste should be disposed of in these bins, since the intention is that the associations of recyclers work hand in hand with the groups, companies, buildings and other people from the different areas to help them take out what they are reusable and what is not” (para. 7).

The foregoing reflects that once again the recovery of waste and the respective alliance with the rest of society is being left solely under the responsibility of the recyclers when the District Administration should be more forceful in the formal inclusion of recyclers in the new underground container strategy.

The most recent public furniture of the Bogotá sanitation system has a greater capacity, going from 3,200 liters of old containers to 6,400 liters of only unusable material, since collecting this type of material is its only objective, according to Luz Camacho, director of the UAESP (Editorial Nation, 2022).

Engineer Anderson Reyes, analyzing the new containerization strategy, highlights some of the advantages in terms of improving landscaping and that by preventing them from being improperly arranged on the street, they will stop contaminating natural water sources and rainwater channels. Likewise, it said that “negative aspects may arise due to the low levels of culture of separation between usable and non-usable waste, and for this reason the pressure on the Doña Juana landfill could increase, reducing its useful life” (Editorial El Time, 2022), a situation that is now foreseen, will leave recyclers at a disadvantage, will increase the environmental impacts due to waste contrary to the T724 Sentence, the goals of the 2030 Agenda, the National Policy for Sustainable Production and Consumption , among other.

The most frequent complaints by citizens regarding the containers, according to the report of the Comptroller of Bogotá (2019) in terms of improper location and use, is that these are overflowed by different materials and waste that do not correspond to the initial destination that was given to them and are arranged in places that impede mobility and put pedestrians at risk, complaints that coincide with the assessments of the OROs and the citizens surveyed.

According to annex 11 of the UAESP for the activity of collecting solid waste through containers in Bogotá, sanitation operators were asked to define the best alternative in terms of location, based on mitigating critical points of accumulated ordinary waste or inadequately presented in public space, and according to the report of the Comptroller of Bogotá (2019):

the technical annex establishes some guidelines for the installation, the actions for the collection of usable material, the placement of the containers at 150 meters, that are not located near parks or schools, that do not affect the educational community, among others. But according to the cases received and the tours made by the localities, this is not fulfilled (Contraloría de Bogotá, 2019. p. 4).

In this regard, one of the ORO also stated the following:

Before establishing the strategy, we warned that the containers would become critical points and time has proven us right. Citizens do not consider the colors and deposit all kinds of waste in the containers. In the container with a white lid, you will find rubble, ordinary and recyclable, and the same with the one with a black lid (GAIAREC, 2021).

The different assessments of the OROs lead to the conclusion that the containerization activity has structural flaws in that its appearance, color, and size do not encourage separation, nor does it facilitate the work of recyclers. An aspect analyzed as fundamental by this research group is the fact that the recycling container is smaller than the one for non-usable waste, this flatly leads citizens to deduce that the waste with recycling potential is from less than the ordinary ones, when more than 80% of the waste is potentially recyclable (Vargas, 2021).

The coincidence between the actors under study, in the different questions raised, was the lack of training processes for citizens, as well as the insufficient control by the operators of the cleaning service and the competent entities, so that citizens properly carry out the separation of waste, because although there are rules that regulate the obligation of these actions and fines for violating the rule are established, there is no evidence of control mechanisms to advance in this matter.

As already pointed out by the School of Journalism of the UAM (2019), what leads to the success of a cleaning scheme and recovery of potentially education and citizen culture, accompanied by adequate urban furniture of cleanliness, government regulations, pedagogy, awareness and social incentives”. Regarding the need to increase incentives, such as reducing taxes and/or fees for those who comply with comprehensive waste management in its source separation phase and fining or increasing taxes for those who do not; Likewise, it is imperative that it be done in parallel with the location of furniture in the city, as well as with training processes.

Conclusions

The lack of knowledge about the waste that is usable and the respective separation at the source has the consequence that circular economy processes are not really applied, because by depositing unsuitable waste, potentially reusable waste is contaminated and cannot be used as raw material. within the production process. In addition, the task of recyclers becomes more difficult, as their only source of income is affected. Awareness and environmental education campaigns are required by government entities such as the UAEPS, the Ministry of the Environment and the District Environment Secretariat, as well as by the operators in charge of collection and final disposal.

From this perspective, it is evident that the present containerization strategy or system for the disposal of solid waste is focused primarily on the collection of waste, but it is urgent to establish a system of awareness and incentives with users, in relation to the separation in the source, which has not worked and in some cases the result has been contrary to what was sought, exacerbating the problem of waste in Bogotá.

Regarding the lack of incentives, although it should and responsibility towards the environment and society, every Bogotans should properly manage waste, experience shows that incentives and taxes on those who do not recycle have guaranteed the recovery of more than 50% of the recycling in some countries (Montes, 2019).

No significant progress has been identified with the containerization activity, and on the contrary, there is evidence of a delay in the city of Bogotá regarding the use of waste and its final disposal. For several years it has been reported that the production of waste in the city remains without significant changes, 7500 T are generated daily, of these 6500 T, go to Doña Juana and on average 1200 T are recycled, it would be expected that the strategy of containerization will show an increase in the amount of waste recovered daily, but this is not the case, indicating that the goal of the Development Plan related to delivering in 2020 a capital city where a recycling model with better use of waste will be consolidated. waste, debris and rubbish.

The figures on the amount of waste that is generated in Bogotá and that which is currently recycled, show that the objective of recovering at least 50% of all usable waste that goes to the Doña Sanitary landfill has not been met. Juana, as pointed out by CJS Canecas (2019).

As pointed out by some Bogotans surveyed and leaders of recyclers’ organizations, the result of containerization has not shown a step towards modernization in the provision of sanitation services in Bogotá, given that neither the presentation of waste has improved, nor has prevented the accumulation of these, nor is there evidence that it has promoted recycling, as pointed out by the UAESP (2018).

It can be noted that although the main objective of the containers with a white lid is to facilitate and increase the use of recoverable materials, as stipulated in Annex No. 11 of the UAESP Public Tender (2017), it is for the recyclers of the city who are responsible for intervening directly in these containers, however, for most of the leaders of the associations of recyclers interviewed, this objective is harmed by the lack of citizen culture and environmental education.

The ORO leaders point out that the UAESP’s commitment to which recyclers would be the only ones authorized to collect and use the usable material, according to the routes and associations corresponding to each ASE, has not been fulfilled, since any person can access the containers.

The cleaning and maintenance of the containers located in the different parts of the city have flaws, since damaged containers, without lids and often with bad odors, are identified in different areas. The containerization activity has not mitigated the generation of vectors, the spread of waste, or the appearance of sources of contamination, which affect and deteriorate the harmony of the urban public space, as proposed by the UAESP (2017).

If structural measures are not adopted in terms of solid waste management, Bogotá DC will continue to reinforce the waste production rate forecast by the World Bank (2018) of 3,400 tons per year worldwide by 2050, failing to meet the goals of the Agenda 2030 in relation to SDGs 11 and 12, this situation being also an obstacle for the development of the National Policy for Sustainable Production and Consumption, since naturally if one of these management steps is blocked, the chain is broken, becoming an impediment for the development of said policy and others that in this matter are raised for the city and for Colombia.