IS THE POLITICAL WILL SUFFICIENT FOR THE PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING TO BE SUCCESSFUL?

¿ES SUFICIENTE LA VOLUNTAD POLÍTICA PARA QUE TENGA ÉXITO EL PRESUPUESTO PARTICIPATIVO?

Abstract

The objective of this work is to empirically confirm, through the analysis of municipalities with Participatory Budgeting in the Valencian Community after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019, that political will is a fundamental element for the implementation and continuity of Participatory Budgeting experiences. The methodology used combined qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. The results showed that political will is an important variable for the implementation of the experiments, but that its continuity can be a problem if other elements are not incorporated. The OP, however, is not a global policy of any political party, although citizen participation is a strand most found among leftist parties. Thus, these parties are the ones that most initiate Participatory Budgeting experiences.

Key words:

budget participation, municipalities, Valencian Community, participatory democracy..Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es confirmar empíricamente, por medio del análisis de los municipios con Presupuesto Participativo en la Comunidad Valenciana después de las elecciones municipales de 2015 y 2019, que la voluntad política es un elemento fundamental para la puesta en marcha y la continuidad de las experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo. La metodología utilizada ha combinado técnicas de investigación social cualitativas y cuantitativas. Los resultados han demostrado que la voluntad política es una variable importante para la puesta en marcha de las experiencias, pero que, para su continuidad, puede ser un problema sino se incorporan otros compromisos. Sin embargo, no es una política global de ningún partido político, aunque la participación ciudadana es una política más integrada en los partidos de la izquierda, siendo estos los que ponen en marcha más experiencias de Presupuesto Participativo.

Palabras clave:

participación presupuestaria, municipios, Comunidad Valenciana, democracia participativa..INTRODUCTION

A little over three decades ago in the city of Porto Alegre (Brazil) one of the most recognized and widely spread democratic innovations in the world was born, the Participatory Budget. Being thus recognized by international organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the UN, and by governments of all latitudes, which have implemented it and adapted it to the characteristics of each country (Pires & Pineda, 2008), having produced a diffusion of the model that has reached all continents. According to what was published in 2019 in the World Atlas of the Participatory Orçamento , there were at that time more than 12,000 experiences underway, with Europe being the continent with the most experiences (4,600) and Spain the third country with the highest number (350-400). ) behind Poland ( 1840-1860) and Portugal (1686) .The isolation measures, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have led many governments to interrupt or terminate the ongoing participatory budgeting processes, which has caused the first decrease in the number of budgets in the 30 years of operation. of experiences, up to 7,976 and changes in the methodology of those that have remained (Dias et al., 2021). Interestingly, the areas of the world that have always been considered to have democracies with greater citizen participation are the ones with the least experience of the PP.

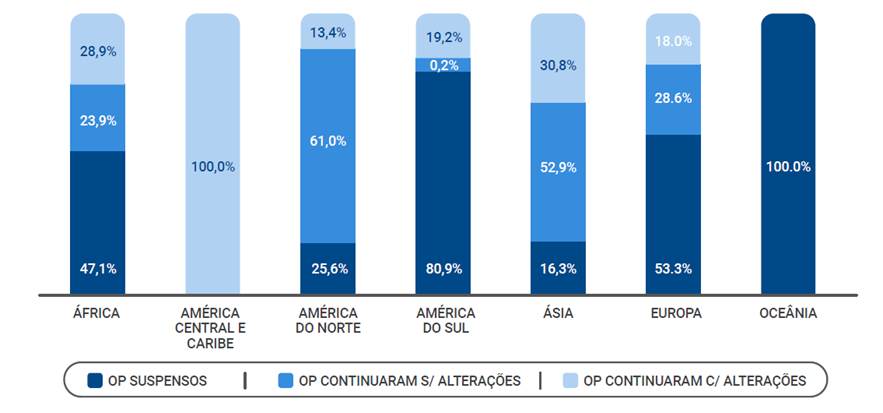

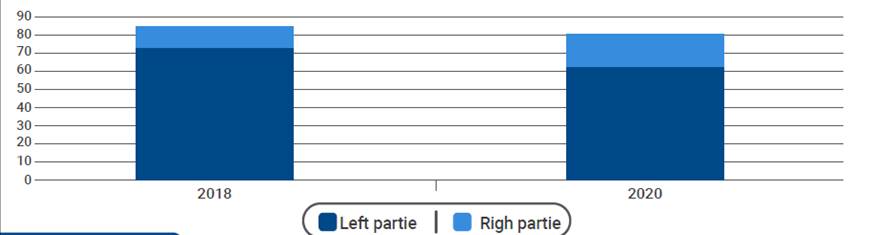

Graph 1 shows the changes produced in the continents with reference to the experiences of participatory budgeting due to the pandemic.

Figure 1: Participatory Budgets in the world in times of pandemic

In Spain, the Participatory Budget (Ganuza, 2007; Pires & Pineda, 2008; Ganuza & Francés, 2012; Mayor, 2018; Pineda & Andrade, 2018, cited by Nebot et al., 2021) was implemented in three municipalities, which they are Cabezas de San Juan, Rubí and Córdoba in mid-2001, all this because they were commanded by the leaders of the United Left (Pineda, 2004); for this reason, it was implemented in other municipalities until municipal voting was held to elect the rulers in 2015, resulting in the victory of the left, generating multiple experiences after the municipal elections that also were carried out in 2019 (Nebot et al., 2021).

While the experiences spread, so did the articles, books and communications that were published on the subject, one of the most recurrent issues being the conditions or variables that condition the adoption of the PP by the municipalities. The literature has pointed out during all this time, at least four main dimensions that can help explain the adoption and maintenance of PP, which are: the political will of the rulers, local associationism, institutional design and financial governance (Wampler 2005, 2008; Lüchmann , 2003; Pires, 2011; Goldfrank , 2006; Horochovski & Clemente, 2012; Souza, 2015; Font et al., 2014; Fedozzi et al., 2020; Cabannes , 2020; González & Soler, 2021; Souza, 2021; Lehtonen, 2021). Being the political will, that is, the degree of commitment of the rulers to share with the citizens the power of decision on how to invest the resources of the public sphere, one of the main variables (Fedozzi 2000; Fernández & Pineda, 2008; Lüchmann 2014; López & Gil-Jaurena, 2021).

But despite the fact that political will has been referenced as one of the main variables for the creation and maintenance of PP experiences, not much research has been carried out that deals with this issue empirically in a wide territory (country, state or region). The purpose of this study is to analyze the variable political will in a territory (Valencian Community) from two different periods: after the municipal elections of 2015 and 2019. In order to also verify if the necessary will to start up and maintain a PP experience is that of the entire municipal government or only of a member of the government, if the decision responds to a global strategy of the political parties or if it is an individual decision and if its implementation responds to an ideological issue, for which they are the left-wing parties are the ones that mostly implement PP experiences, or it is already generalized (Pineda, 2010; Fedozzi et al., 2020).

In the methodology, techniques have been combined from social research with a mixed approach (qualitative and quantitative), with the review and analysis of the websites of the municipalities to know if there were experiences of PP, a content analysis of the electoral programs of the main political parties with municipal representation in the Valencian Community and the institutional documentation together with a bibliographic review on the PP of authors from different countries with special reference to Brazil, the country of origin of the experience.

From the respective analyzes associated with the results, it has been verified that political will, although necessary, is not always sufficient, since a process as complex as the PP causes many tensions and conflicts and requires, if it is to function and be maintained, to summon more actors. Also, the importance of ideology at the time of the implementation of an experience, being the leftist parties the ones that mostly implement them, although there are experiences in municipalities administered by political parties of the center or right. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that the implementation of participatory budgets is not part of a national or regional strategy, nor of a strategy of a particular political party, but rather is due to an isolated exercise, of a person, who does not necessarily have continuity in the exercise of an elected position of the same political party. It is even frequently evident that in local governments in coalition this PP process is delegated to minority formations, or that even, in corporations dominated by a party, it has little receptivity among other departments other than the one that starts it.

Theoretical reference

From the beginning of the PP, the authors who evaluated the new experiences considered political will as one of the fundamental elements for its application and success. Understanding the political will to launch a PP experience as the degree of commitment of the rulers to share with civil actors the power of decision on the way in which public resources are allocated. The reason associated with this is that the municipal budget is always prepared and approved by the elected, regardless of the local political system of the countries, therefore, if they do not decide to allow citizens to join the budget process, it could not occur.

The PP are born due to the creation of a bet of a political team regardless of whether it is supported or not by the other government teams (Allegretti et al., 2011). In order to be carried out, the participation processes must have that political will so that the process is successful and the fulfillment of the commitments towards the population (Cabannes , 2004, cited by Mayor, 2017).

One of the authors who has written the most on the issue of political will was Leonardo Avritzer (2009). According to Avritzer, political society, within participatory institutions, connects the rooted conceptions of participation, generated in the formation of leftist and mass parties. Thus, the greater or lesser political will of the rulers to introduce and give continuity to local participatory institutions is associated with the dilemmas, generally faced by leftist and mass parties with a social democratic bias, between maintaining their sociopolitical identity and simultaneously becoming competitive in the political system (Avritzer , 2009, p.13).

On the other hand, Wampler (2007) develops an interpretive line that points to the conjunction between the motivations for the creation of the PP and the political dividends that may return to the protagonists of the municipal government, the mayor, the councilors and the political parties that make up the government. This axis of analysis has the characteristic of considering the PP as a constitutive element of the political-partisan actions of local political societies, that is, internally to the disputes inherent in this field.

Avritzer’s approach was criticized by Romão (2011) who considered his vision of the role played by political parties in the PP strategy to be limited. That is why Romão in later works, instead of using the psychological variable “political will”, substitutes it for the category of “political status of the PP “ in the municipal government. The political status of the PB strategy in the context of the municipal administration, in his opinion, has a strong connection with the location of the government structure, which performs the function of coordinating the process for participation, and also with political capital. of your coordinator. On the other hand, Romão (2011) believes that the work of Wampler (2007) opens an important line of research to deepen the discussion on the political conditioning factors of the creation and maintenance of the PP by the public power.

Subsequently, Mayor & Alarcón (2020), among other authors, point out that in addition to political will, other commitments are necessary To implement and maintain a PP experience: i) the agreement of all the political groups to respect the procedure without interfering with the elections in the continuity of the participatory budget ; ii) the commitment to public officials and public service workers to participate in a new commitment to society; iii) the commitment to integrity and public ethics that is included in a code that everyone accepts and commits to; iv) opening the institutions so that citizens can participate and know the decisions; v) have a team that stimulates the collective practices of control and prioritization of public spending; and vi) the existence of a citizen council elected by lottery each year to serve as a control body for the process.

But, although the conditions for launching a PP experience have been expanded over time, the political will of the municipal government is still considered essential. In general, perhaps because most of the investigations are case studies, a broader analysis of that political will has not been planned, which is what this work is intended to achieve.

Another important issue is to analyze the ideology of the governments that launch PP experiences. Initially it was strongly associated with the left and framed as part of a social justice agenda (Baiocchi & Ganuza, 2014), although with the global spread of the PP, this is fading as it is also used by right-wing and center governments. Despite this, many authors consider the ideological dimension crucial to understand its possibilities and limitations. The PP was originally part of a leftist project that aimed at profound social transformation, which does not happen in governments of another sign that use it as a mechanism to improve management (Holdo, 2020).

The United Left in Spain was the one that began with the implementation of participatory budget processes, currently all political forces use them, although it is possible to observe differences in their objectives, in the type of methodology used and in their intensity (Greater , 2016, p. 7). Therefore, this tool is not the property of any of the political parties, although the experiences in municipalities governed by left-wing parties or coalitions continue to be the majority (Pineda, 2010; Cernadas et al., 2013; Galais et al., 2011; Mayor & Alarcon, 2020).

Based on what has been exposed, we can formulate the following research hypotheses:

H1: Participatory Budgets in the Valencian Community are launched by the political will of the mayor or some member of the municipal government.

H2: The PP is not a global policy of political parties.

H3: It is mostly the leftist parties that launch PP experiences in the Valencian Community.

H4: The experiences disappear when the political sign of the municipal government changes.

Methodology

The methodology used combines qualitative and quantitative social research techniques through which the situation of the Participatory Budget in the municipalities of the Valencia Community can be known in two different periods, after the municipal elections of 2015 and those of 2019, and compare them. For this, the web pages of the municipalities, the electoral programs of the main political parties with municipal representation in the Valencian Community and the institutional documentation have been reviewed and analyzed together with the necessary review of the literature of authors from different countries.

The object of analysis of the investigation has been the municipalities of more than 4,000 inhabitants of the Valencian Community, one of the 17 communities in which Spain is divided, having chosen the cut in this number as no experiences were found in municipalities with a lower census to this figure 2.

Figure 2: Political map of Spain.

The Valencian Community is the fourth autonomous community in Spain by population and represents 10.7% of the country's population, being divided into three provinces: Alicante, Castellón and Valencia. This community has been governed by the Popular Party for twenty years. In addition, it is currently one of the Spanish communities with the largest number of PP experiences.

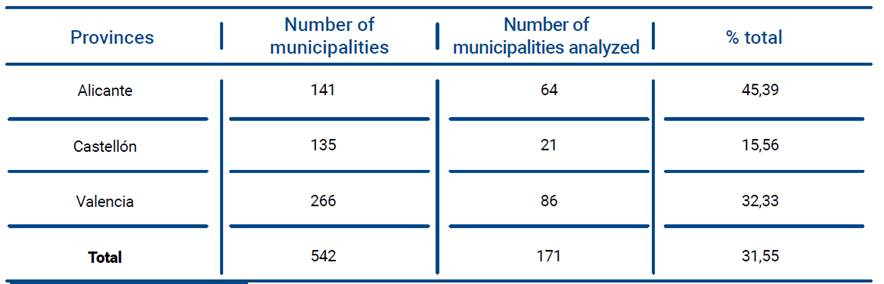

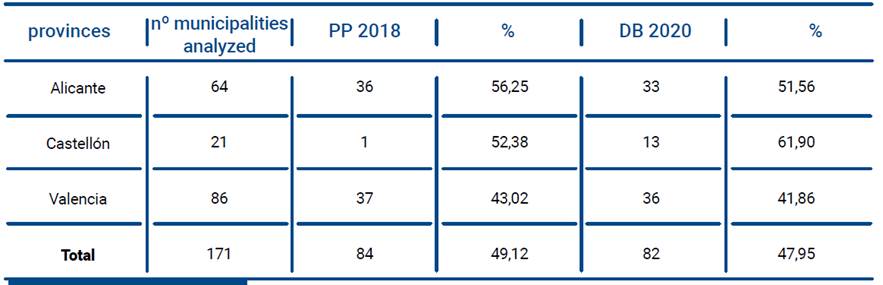

Table 1 offers data corresponding to the total number of municipalities by province of the Valencian Community, the total number of municipalities investigated, which amounts to 171, and the percentage of municipalities analyzed.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 1: Total number of municipalities by provinces and municipalities analyzed.

These data indicate that 31.55% of the total municipalities of the Valencian Community have been analyzed, the highest percentage being in the province of Alicante (45.39%). This occurs because the other two provinces have a greater number of municipalities with less than 4,000 inhabitants, that is, small-sized municipalities.

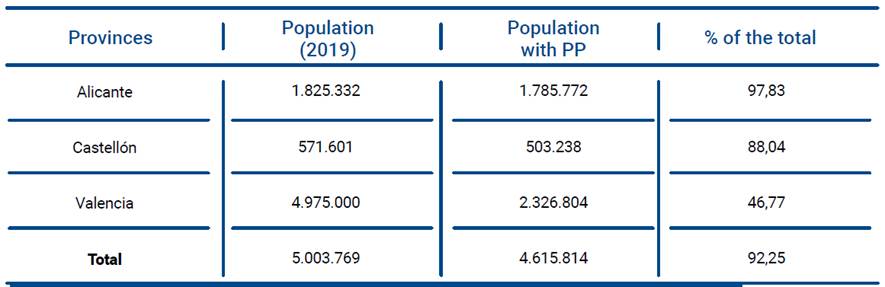

In Table 2 we can see the total population and by provinces of the Valencian Community, the population with PP and the percentage of the population with PP of the total population.

Source: own elaboration based on population data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) (2021).

Table 2: Population of the C. Valenciana and population with PP.

Looking at the population data although 31.55% of the municipalities have PP, they account for 92.25% of the total population of the community. Valencia being the one with the lowest percentage and Alicante, with larger municipalities, the one with the highest percentage.

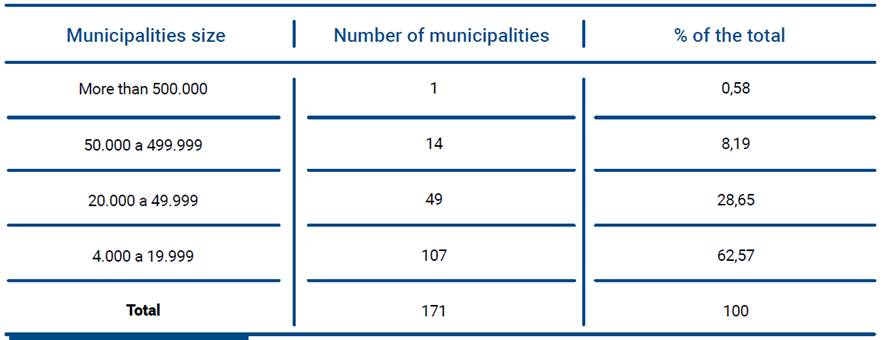

In Table 3 we see the size of the municipalities analyzed and the percentage that corresponds to them from the total of them.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 3: Size of the municipalities under analysis.

Regarding the size of the municipalities, the majority (62.57%) are municipalities that range between 4,000 and 19,999 inhabitants, that is, of medium-low size.

The field work was carried out in two stages: the first involved the collection of data and the second its treatment. The data was collected through a process of systematic observation of the municipal portals. The data collection chronology was carried out in two periods: the first from December 2018 to January 2019 and the second from December 2020 to January 2021.

Results and Discussion

n the World Atlas of the Participatory Orçamento (Días et al., 2019), whose main objective is to inventory the experiences of PP in the world, 12,000 experiences were found, with Europe being the region of the world where there were more experiences (4,600), number which has decreased during the time of the pandemic (Dias et al., 2021). In Spain, the number of experiences has been growing during the 20 years that they have been with us, although with strong oscillations, being from the municipal elections of 2015 when there has been a greater growth, due, among other reasons, to the arrival of the so-called governments of change. The municipal candidates presented themselves as those with new practices in the way of doing politics, which involved citizen involvement in management through the development of shared information and decision-making spaces, however, it would be false to affirm that they have initiated the participatory public policies in Spain (Mérida & Tellería, 2021).

According to the 2019 Atlas data, the Valencian Community had between 20 and 25% of the Spanish PP experiences, a number that, as can be seen in Table 4, has been maintained after the last municipal elections, although with a small decrease and that they account for almost half of the municipalities studied. This shows that there is a great interest in this community to implement Participatory Budget experiences. It would be interesting to analyze the situation after the next elections in 2023, to find out if the experiences continue despite the entire period of the pandemic.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 4: Municipalities with a Participatory Budget in 2018 and 2020 in the C. Valenciana.

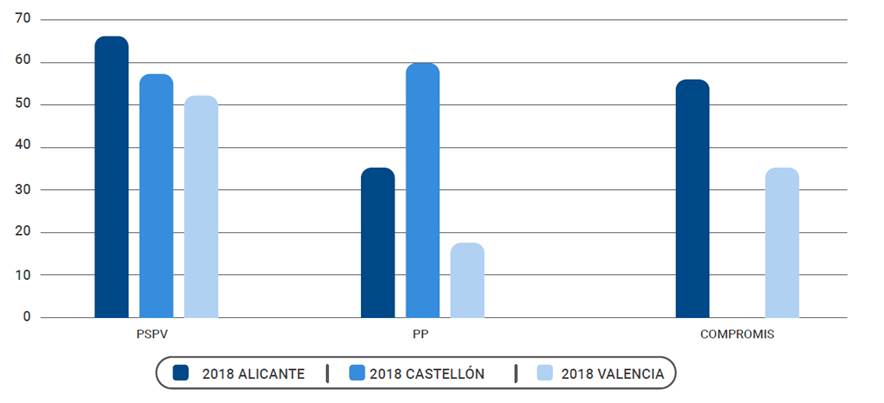

If we take into account the percentage of municipalities governed, as of 2015, by one of the three majority political parties in the community (PSPV, Partido Popular and Compromis) in relation to the number of municipalities analyzed that govern each of the provinces, we see in Graph 2 that in 2018 the two leftist parties (PSPV and Compromis) have greater representation in the province of Alicante and that instead the Popular Party has greater weight in the province of Castellón, which is the smallest of the three provinces .

Graph 2: Percentage of analyzed municipalities governed by each political party in 2018.

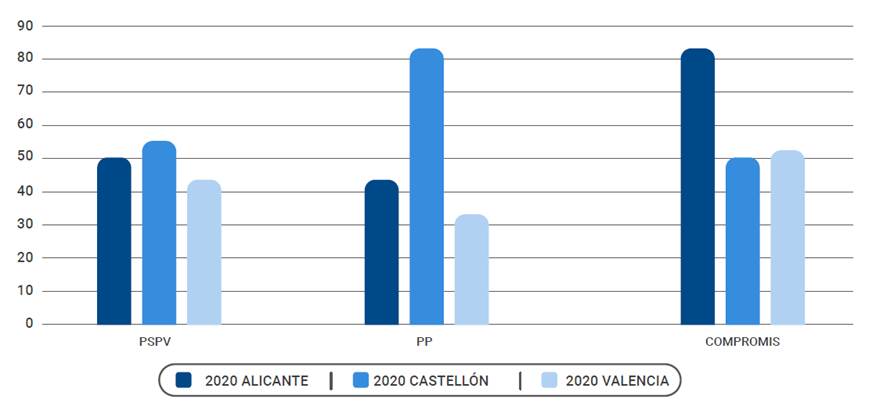

Graph 3: Percentage of analyzed municipalities governed by each political party in 2020.

The situation changes after the 2020 elections, recovering in Alicante and Valencia the power that the Popular Party had had for the last twenty years, the PSPV descends in the three provinces and Compromis increases it in all three. Despite these changes, there is not a great variation in the number of PP experiences.

Despite the decrease in the percentage of municipalities governed by the PSPV after the 2019 elections, the population governed by this party did not decrease as much, going from 54.7% in 2015 to 49.7% in 2019. The Popular Party, despite increasing the percentage in the province of Castellón, it fell from 8% to 6.3% of the population. Only Compromis increased its percentage of the population, from 37 to 44%, thanks to the advantage achieved in Alicante and Castellón. Which means that, although the PSPV lost the government of some municipalities, it continues to govern almost 50% of the population of the community.

But these data do not help us to know if there have been changes in municipal governments and if these changes have influenced the maintenance or disappearance of PB experiences. For this , the different political changes produced by an election must be understood and if these changes have influenced the PP.

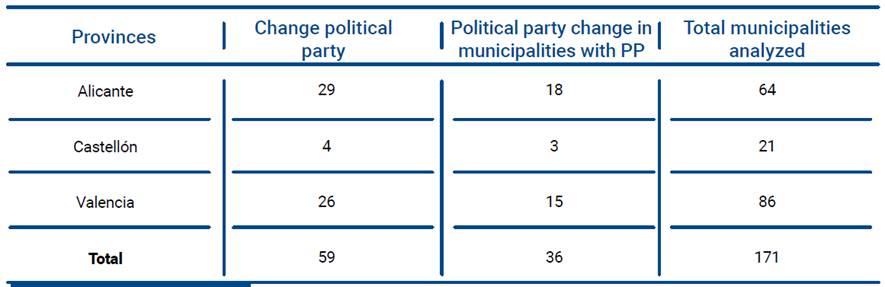

Table 5 shows the changes produced in the different municipalities analyzed after the 2019 elections, both in the municipalities that had PP and those that did not.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 5: Political party changes after the 2019 municipal elections.

In the municipal votes of May 2019, 59 municipalities of the Valencian Community changed the political sign of their mayors, which represents 34.5% of the municipalities analyzed, with the province of Alicante being where there have been more changes (45.31%) and that of Castellón where less (19%). On the other hand, in those municipalities in which there is a PP experience, there have been fewer changes, only 21% of the total number of municipalities analyzed have changed their political sign. It would be necessary to analyze in depth if the PP has been a factor of continuity for the ruling political party or if the reasons have been other.

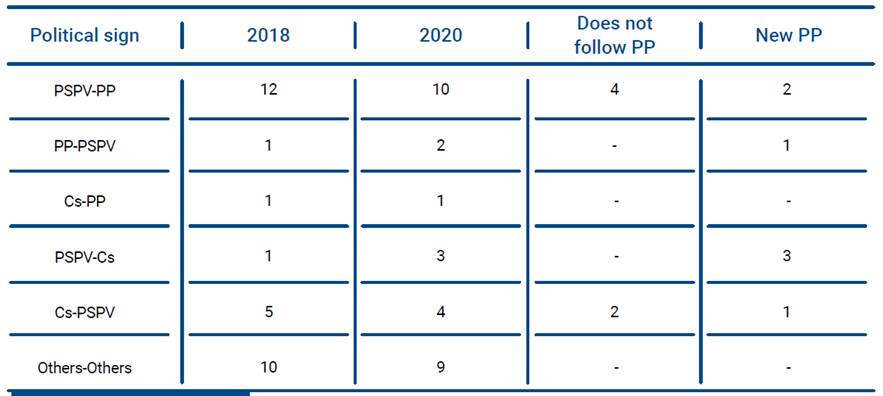

Of these changes, the most significant as can be seen in Table 6, since they are left-wing parties to a right-wing party, are those of the Socialist Party of the Valencian Community ( PSPV) and Compromises to the Popular Party. In the case of the change from the PSPV to the Popular Party (14 municipalities), four of the PP experiences have not continued, but two new experiences have been launched. From Compromis to the Popular Party there has only been one change and there the PP experience has been maintained. In the changes between the PSPV and Compromis (3 municipalities) we have appreciated that the experience that existed has been maintained and that they have been created in the municipalities that did not have them. The same has not happened when the municipalities have gone from being governed by Compromis to being governed by the PSPV, since two of the ongoing experiences have ended. This goes to show that the change of political sign of the municipal government does not always imply the elimination of the experience, although it occurs more frequently when it goes from a leftist government to a conservative one. At this point, it would also be interesting to know the reasons for the change in the political sign of the municipal government and how it has influenced both the continuity of the PB process and its objectives and methodology.

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Table 6: Changes in the political sign of municipal governments.

We also wanted to analyze, in order to find out if the political decision to launch or continue a PP experience depended on the political sign of the mayor, those cases in which the same political party remained in the municipal government, but despite this Changes were made after the 2019 elections. We have found ten municipalities that considered PP experiences to be finished and another ten that started them, maintaining the same municipal government party. In the case of the municipalities that terminated the PB experiences after 2019, we have found that most have been due to changes in the person leading the experience, be it the mayor or a councilor. In the case of the councilors, one of them was from the same party as the mayor, although in most cases they were councilors from another party who governed in coalition with the majority party, through a legislature pact, and who did not leave elected at the next election call. Something similar happens when it is decided to launch a PP experience. Other reasons for the end of the process are the difficulty of managing the proposals or the decision that the money that was used for the PB go to a single proposal. In the only case that we have found of the Popular Party, the explanation of the experience is the hiring of a consultant to implement a project-type initiative associated with transparency and open government, a project in which the PP is included.

In order to find out if the decision to launch PP experiences is a global proposal of the political parties or they are isolated proposals of municipal politicians, we have carried out an analysis of the municipal framework programs of the three main political parties with representation in the Valencian Community of the elections of 2015 and 2019, having appreciated that in none of them there is a clear reference to the PP or an application proposal, as if it happened in other previous municipal elections. This does not mean that the PP is not referred to in the specific electoral program of some municipalities, but it does show that the PP is not a general party policy.

Despite this, there are differences between some programs and others. In the PSOE of 2015 there is talk of making public the information related to budget items and in the section on young people it refers to the possibility of sending their proposals to the participatory budgets. In the 2019 report, reference is made to the transparency of public accounts, to the holding of citizen assemblies in which management will be accounted for and complaints, suggestions or contributions will be collected. by the citizens and, there is also talk that the draft of the municipal budgets that will reserve an annual amount for investments that will be decided directly by the neighbors will be submitted to information and debate. in participatory processes, in which the proposals will be selected and voted on, which will finally be taken to the final budget items. The latter, although it does not receive the name of PP, is really a PP.

In the Compromis there is no reference to the PP, but to citizen participation when they refer both to its economic model and to the different public policies. In addition, they point out that they will promote an Open Government Law, which opens the doors of the administration to citizens, encourages their participation in decision-making and guarantees transparency in the management of public money.

In the 2015 Popular Party program there is no reference to the PP or to participation in the budget. Regarding participation, they point out that they will promote the improvement and application of regulatory instruments and citizen participation mechanisms to achieve greater interaction between municipal officials and residents, emphasizing the use of ICTs for this. In 2019 there are no such references, it is a program focused entirely on the economy.

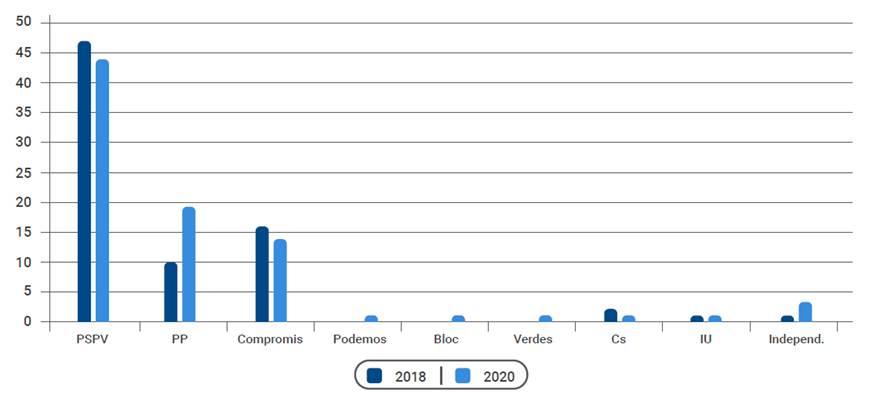

Another issue that we analyze is whether the political decision to launch a PP experience depends on the political sign of the municipal government, whether it is those municipalities governed by left-wing parties that apply these projects the most. As can be seen in graph 4, the largest number of experiences in the two legislatures are found in municipalities governed by the PSPV (58.75% and 53.66%), although after the 2019 elections the number of experiences decreased (10 experiences). The other two parties that have a significant number of experiences are Compromises, which went from 14 to 16 experiences, and the Popular Party, which went from 10 to 19 experiences, which represented a significant increase.

Graph 4: PP experiences by political party in 2018-2020.

As can be seen, there are experiences promoted by both leftist and conservative parties, which demonstrates the ideological heterogeneity of the project. Although most of them occur in municipalities governed by left-wing parties, as can be seen in graph 5, what has happened since the beginning of the implementation of PP experiences in Spain (Pineda, 2010). Without forgetting, furthermore, that it was a left-wing party, Izquierda Unida, which brought the first experiences of PP to the Spanish municipalities, having the city of Córdoba as its main reference.

Graph 5: Number of PP experiences according to ideological orientation.

These data confirm that it is the left-wing parties that mostly launch PP experiences, although there are already parties of another political bias that do so, albeit in a minority.

These data confirm all the hypotheses raised. The first is that all the experiences of the Community are launched in accordance with the political will of the government, be it the mayor or a councillor. Councilor who can be from the majority party or from the minority party in the case of coalition governments. The second is that its implementation is not part of a general policy proposed by any political party, but rather they are individual proposals by elected mayors or councillors. The third is that it is the municipalities governed by political parties with a left-leaning tendency (PSPV or Compromise) that mostly launch PP processes, although more and more municipalities governed by the Popular Party also do so. Finally, it is important to point out that most of the time the experiences disappear when the political sign of the municipal government changes, but it can also occur for other reasons.

Conclusions

All the experiences analyzed in the Valencian Community are born from a political decision of the municipal government, since there is no provision in the Spanish legal system, except for the “Large Cities” Law, any precept that includes the participation of citizens in decision making. budgetary measures, as is the case in other countries such as Peru since 2003, the Dominican Republic since 2007 or South Korea since 2011.

This political decision can be promoted by the mayor or a councillor, which means that it may or may not have the support of the entire government. In the case of some coalition governments, the minority partner is usually the one that promotes the PP project, with the negative consequences for its operation that this situation causes, as the other members of the government feel that it is an imposition. Another negative aspect that is perceived in some experiences is the identification of the process with the party that starts it, which causes a loss of its potential and its disappearance when the political sign of the municipal government changes. To solve this issue, it would be interesting for the government team to involve the opposition in the project.

And although the impulse of the PP responds in all the municipalities to a certain political will, because otherwise they would not be carried out, there is generally little political commitment. It is evident when seeing that this type of experience tends to be residual within the government structures, being in charge, in most cases, of its management the councilor or councilor of citizen participation. In addition, there is usually little involvement of the different departments of the local administration affected by the results of the process, a fact that greatly hinders both the development of the process and the execution of its results.

In the analyzed municipal programs, from the 2015 and 2019 elections, of the three main political parties of the Valencian Community, no specific reference is made to the Participatory Budget. This shows that launching a PP experience is not a global strategy of any political party. However, in the framework program of the PSOE for the municipal elections of 2019 there is talk that the draft of the municipal budgets that will reserve an annual amount for investments that will be decided directly by the neighbors will be submitted to information and debate. in participatory processes, in which they will select and vote on the proposals that will finally be taken to the final budget items. The latter, although it does not receive the name of PP, is really a PP.

Despite not mentioning the participatory budget in any of the programs of the three parties, it is important to point out the differences between the programs of the PS PV and Compromis and that of the Popular Party in terms of citizen participation, in the first two there are clear references to the role that citizens should have in the management and government of the municipalities and in those of the Popular Party there is little mention of the subject and when it is done it has a very normative nature and is related to ICTs. Despite this, the three parties are launching experiences in some of the municipalities they govern.

The data also confirm that the left-wing parties are the ones that mostly launch PP experiences in the Valencian Community (72%), although parties of another political bias also do so, although more minority. Perceiving clear differences in the objectives of the experiences according to the ideology of the municipal government.

It is also observed that those PPs that arise from a political decision based more on a trend or “fashion” than on a conviction about the advantages of citizen participation, that is, they consider it more of a neutral technical tool of good governance more than a political institution ( Wampler & Goldfranck , 2022, p. 12), they tend to use the internet as the only way to participate, using ICT only for collecting proposals, as if it were a mailbox.

The “politicization” of the PP, as we have already pointed out, has both negative and positive aspects. Having political backing can strengthen commitment and ensure adequate resources, but it also creates critical vulnerabilities that can affect long-term sustainability. It has been verified when analyzing the data that the identification of the proposal with a specific political party can ruin its future, some experiences have disappeared not because they did not work well but because when another political party won the following elections it did not want to be related with the project of its predecessors.

The centrality of political will can make a PP process more “vulnerable” compared to other more institutionalized participatory processes. Finding the right balance between all these aspects can be a key success factor in PP processes in all parts of the world.

Finally, note what Yves Cabannes (2004) indicates: “The will has to be maintained throughout the process, but fundamentally it must be specified in the fulfillment of the budgetary commitments contracted with the population” (p. 30). If it doesn’t happen that way, the process tends to create mistrust among citizens and ends up disappearing.